Book Review: On The Edge, Nate Silver

Find the EV maximizer—and degenerate gambler—in yourself. Just be careful not to destroy the world.

In 2016, Nate Silver was panned in the press and on social media for his presidential election forecast. His model gave Clinton a 71% chance of winning, and she lost. He and other forecasters totally missed the Trump phenomena; the polls were off and Trump was more popular than expected. For many people, the bloom was off the rose. Silver—who had so brilliantly predicted all the details of the 2008 and 2012 elections—got it wrong. He wasn’t infallible after all.

The catch is that it was actually a great forecast. The 29% chance Silver’s model gave Trump was significantly higher than most of the other prediction models—some of which gave Clinton as much as a 99% chance to win—and, crucially, much more bullish on Trump than public betting markets in gambling houses around the globe, which thought Trump had about a 17% chance to win. If you believed Silver’s model, it was a blaring siren to bet on Trump and against the conventional wisdom. Those who followed Silver’s advice got a massive return on their investment.

This analytical split—between people who saw Silver’s 2016 forecast as a huge miss and those who understood it as astute and financially lucrative—goes to the core of his fantastic new book, On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything. The world is increasingly divided between two types of people. The first are those who look at Silver’s forecast, see he thought Clinton was going to win, and quite reasonably conclude he was wrong. The second are those who look at the world probabilistically, try to model variables that marginally affect those probabilities, and measure success by comparing their model against prevailing conventional wisdom, regardless of the actual election outcome.

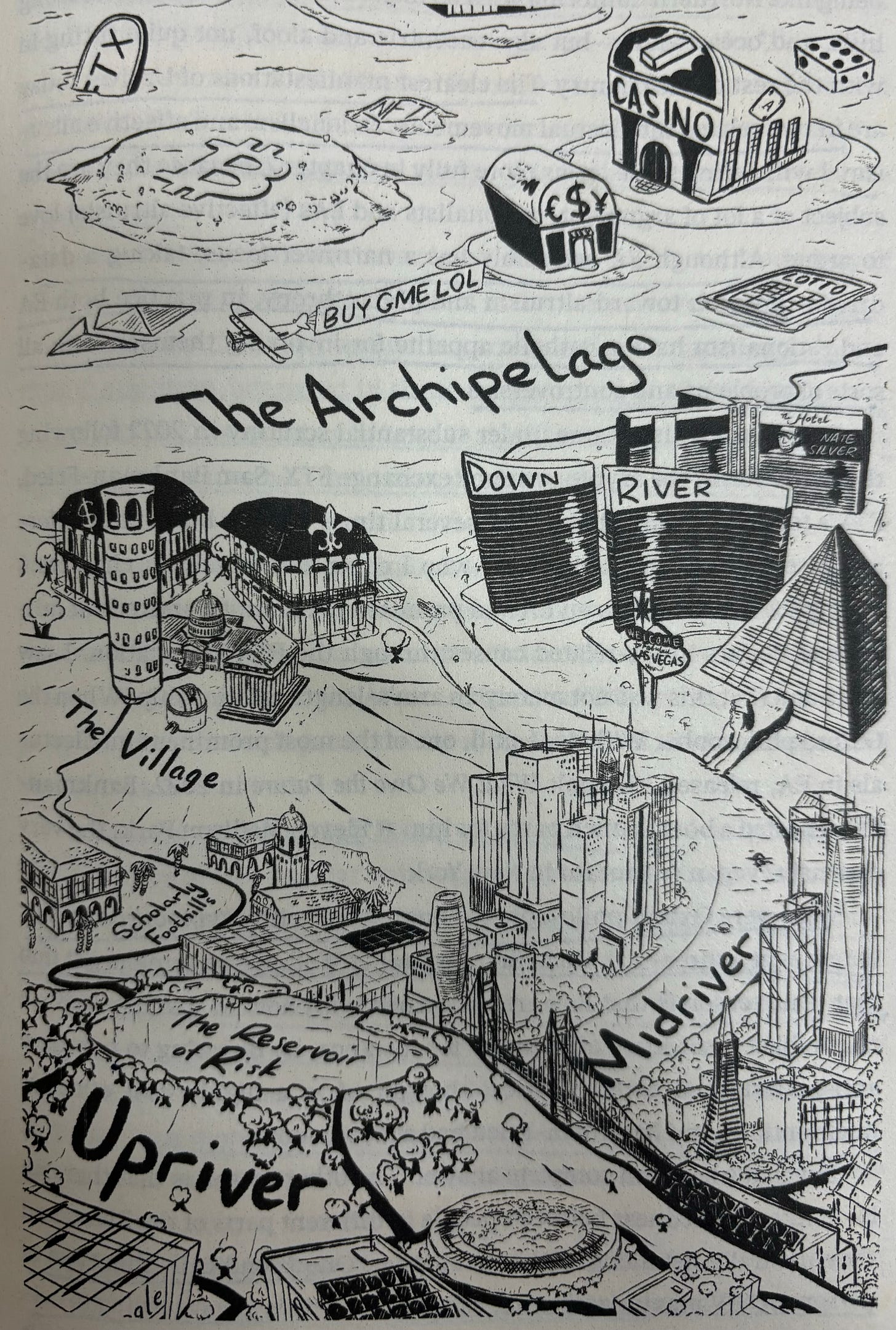

Silver calls the latter group Riverians, after a river analogy he uses to structure the book. These Riverians come from across the political spectrum and are prominent in a wide variety of career fields—on Wall Street, in Silicon Valley, playing professional poker, advising casinos in Vegas, running Effective Altruism charities, and building crypto businesses.

What they have in common is a mindset about risk—they embrace it—and an analytical framework for thinking probabilistically about, well, everything. They live in the world of expected value, marginal utility, game theory, and abstract models. And, in Silver’s view, they are becoming increasingly powerful in society. As tech leaders. As thought leaders. And as political influencers.

In contrast to the Riverians are those with a risk mindset Silver calls The Village. Composed of a wide variety of people but with concentrations in government, academia, and the media, the Villagers are skeptical of markets, more likely to adopt partisan identities (especially center-left politics), more likely to focus on equality as a value and seek to constrain capitalism and meritocracy, and more like to view risk as something to mitigate.

Villagers see The River mindset as too much unbridled capitalism and too little moral concern for the public good. Riverians see The Village as conformist and paternalistic political ideologues whose risk-aversion and culture war obsession are stifling progress on everything from technology to anti-poverty efforts.

On the Edge is structured as a tour through the various worlds of the Riverians. The first half of the book is about gambling—the quintessential downriver activity. There are chapters on poker, sports betting, and the casino industry itself—and the people who are increasingly dominating these worlds through ever-more-sophisticated analytical tools.

The second half of the book goes both upriver—to the more respectable world of Silicon Valley venture capitalist, prediction markets, and the philosophies of Effective Altruism and Rationalism—and further downriver, where unbridled risk and temptation await in the world of cryptocurrency and other gray-market endeavors.

This is an absolutely sprawling book that covers an insane amount of ground in-depth. The kind of project you can’t really imagine an editor greenlighting. It clocks in at almost 500 pages, but the sheer amount of content across so many domains makes it feel like double that. There are explainers, analysis, profiles, and commentary galore. You are going to learn a ton.

Luckily, Silver’s breezy writing and engaging style make it an easy and fun read, not unlike his short-form writing online. Every chapter is substantively enjoyable, and each works as a stand-alone examination of a distinct topic. At many points, I literally couldn’t put it down. Often, the through-line of risk and the larger themes of politics and society are only lightly present, with the focus kept on the inherently interesting characters and worlds they inhabit. The reporting and analysis are top-notch. It’s the kind of book that has something interesting on every page.

At the heart of the book is a simple proposition. Imagine I offered you a choice. You can have $500 no questions asked, or you can roll a die. If you choose the die and it comes up any number but 6, you get nothing. But if it comes up 6, you get $5000.

This book is not about the people who take the $500. But it’s also not about the people who think for a couple of minute and choose to roll the die.

This is a book about the people who instantly grab the die, can’t imagine not instantly grabbing the die, and think anyone who doesn’t instantly grab the die is somewhere between irrational and insane.

Silver, like any good Riverian, would grab the die without hesitation.

The Expected Value Mindset

I grew in an incredibly competitive games-playing family. Card games, board games, parlor games, video games, trivia games. We played for keeps. Didn’t matter if it was chess or spoons. You took it seriously. And you didn’t soft play anyone. Ever. I can still picture my sister, age 7, crying during a game of Pitch because she didn’t make her bid, and my father telling her, matter-of-factly, “you’re never going to get any better if we let you win.”

Same with my friends. Every day after school, we competed. HORSE and Around the World in the driveway, Spit and Gabes and Oh Hell at the card table, Trivial Pursuit and Balderdash and Connect Four at the game table. No mercy, anywhere.

But we also played to learn. Underneath the competitiveness was a collective desire for everyone to get better at these games. We’d spend as much time discussing the strategies as we did actually playing the games. Yahtzee. Authors. Tyson’s Knock Out. Monopoly. Spades. There are winning strategies to any game, and we were intent on finding them. It was half the point of playing. Maybe more. I mean, I’ve been locked in an hour-long argument on Christmas morning about proper Hungry Hungry Hippos strategy. But no one ever held back the secrets. How could we let someone from our crew end up in a game with strangers and not dominate it? That’d be embarrassing.1

Gambling is the natural extension of game playing, and by the time I was a teenager, a layer of it had developed around all this. It was already in the air—I grew up not far from Saratoga, NY and until I moved away I didn’t even realize how much gambling low-key permeated the culture—but it was probably inevitable in any case. We bet on everything. Free throws. Scrabble. Tecmo Bowl. What time the ice cream truck would show up. And, of course, card games. Gin. Oh Hell. Go Fish. Whatever. My dad was a solid amateur poker player, and we quickly found his copy of Seven Card Stud for Advanced Players. Now my friends and I had a new skill to develop. How to hustle people.

As it turns out, this is a classic Riverian background. Games are one of the most pure forms of decision-making under conditions of uncertainty, and tend to reinforce the basic analytical mindset Silver associates with The River: maximizing expected value, or EV for short. Whether you are gambling or investing in the stock market or just trying to wisely choose what route to take to your destination, you are trying to maximize your EV, be it in units of money, time, happiness, or some unspecified combination of all of them.

Take the die roll from above. It’s a highly +EV decision to roll the die. 83% of the time you will get $0 when you roll 1 through 5. But the expected value of the die roll is $833.33 because the 1/6 of the time you roll a 6 you will get $5000 ($5k/6= $833.33). So your net expected value of choosing to roll rather than taking the $500 is +$333.33.

Closely related to expected value is the concept of variance. Sometimes you are willing to forego the highest expected value, in order to avoid extreme outcomes. Imagine if you have two vacation choices, same price. Choice A is a week at a very nice beach in Florida, and the weather is guaranteed to be perfect. Choice B is a week at the most beautiful Greek beach in the Mediterranean, but there’s a 25% chance it will rain and you will be stuck indoors all week.

If you think the sunny Mediterranean vacation is a lot better than the Florida vacation—like twice as good—then it’s a better EV play, even with the chance of rain. Imagine Florida is worth 15 units of value to you, sunny Greece is worth 30, and rainy Greece is worth 4. That makes the overall EV of Greece 23.5 (75% * 30 + 25% *4). But maybe you just want to guarantee a decent vacation, without any rain. That might lead you to choose Florida and lock in 15 units of value. Lowers your EV, but reduces your variance.2

Actually explicitly quantifying all of this may sound foreign to you, but it’s second nature to Riverians. And to me. Games and gambling and EV and variance are almost always how I approach the world. I’ve continued to play serious poker and competitive bridge into my adult life. But games and analytics have also significantly informed my professional work. Politics is not a game, but understanding political institutions as the rules of the game and the behavior of political actors as game-players constrained by the rules is a very profitable way to analyze political situations.

The first half of On The Edge is a trip through the modern gambling world, where EV and variance are most cleanly applicable. The first two chapters focus on poker, which has undergone an analytical revolution in the past twenty years. Once dominated of by gamblers and hustlers who relied on their deep experience and ability to quickly size up their opponents’ strategic tendencies, it is now dominated by gamblers and hustlers who rely on their nerdy ability to program and study the outputs of computer solvers that have identified the unbeatable game-theory optimal (GTO) strategies for the game.

Despite these advances, poker remains a people game. The biggest winners have a superhuman ability to evaluate risk and reward. But they can also manage the stress of betting massive amounts of money, and numb themselves to the prospect of losing six figures on the turn of a card. They also employ an emotional intelligence that allows them to understand and empathize with—but ultimately exploit—their opponents. Even this, however, is informed by the computer work; to maximally exploit your opponents requires a quantified understanding of their strategic mistakes.

Those familiar with Silver’s short-form work will find his usual analytical skills on display here. The writing is crisp and covers a ton of ground—there’s a narrative history of the intellectual development of poker; explainers on game theory and GTO poker solvers; short profiles of a dozen top players including Phil Helmuth, Daniel Negraneau, and Vanessa Selbst; statistical analyses of poker tournament variance; discussions of gender issues in poker; and plenty of personal reflections about his own poker experience.

Perhaps the most surprising aspect of On The Edge is just how deeply personal it feels. If you read Silver’s wonderful first book, The Signal and The Noise, the writing style and the argument have an air of journalistic detachment. Not so with On the Edge, which often reads like a memoir. As it turns out, Silver is more cardplayer than election analyst, much more at home with the gamblers than the political pundits. He also breaks the 4th wall often; early on it’s somewhat jarring. There’s a Hunter S. Thompson gonzo quality to the story, Silver an omniscient narrator but also a participant-observer in an increasingly fantastical wonderland of poker games, casinos, and sportsbooks.

But the choice is ultimately brilliant; the poker hands have an immediacy to them, the stress of a high-stakes poker tournament is visceral, and the interior monologue of the gambler-making-decisions is illuminating. Of particularly note is the sports betting chapter, which is a wide examination of old school bettors, modern line-modeling wizards, and the contemporary sportsbooks they all play cat and mouse with. But it is anchored by an engaging analytic review of the almost $2 million Silver wagered on NBA games while researching and reporting the book (he came out a modest winner on the wagers).

If wagering $2 million on basketball makes Silver sound like a degenerate gambler, you would be correct. But in the rarefied air of The River, degenerate doesn’t have the same negative connotation it once did, when it was reserved for action junkies making -EV wagers and debt-riddled losers.3 Nowadays, it’s also worn as a badge of pride by crushers in the poker and sports betting worlds, signifying someone who chases +EV opportunities to the max, with no concern for variance and little apparent care for money. The score is kept by EV. Not betting a +EV spot is the mortal sin.

The chapter on the casino industry gives the reader the first real feel that The River may not be all fun and games. The analytical approach of Riverians isn’t just for nerds outsmarting the world, but also for massive corporations trying to maximize revenue. Casinos, using ever-more sophisticated data about their customers to fine-tune their gaming offerings, are playing the EV maximization game from the other side of the table. This feels especially dark with slot machines, which grew increasingly -EV for players over the last few decades and appear to have their EV and variance fine-tuned to prey directly on gambling addicts.4

It might feel impossible that casinos weren’t using big data to maximize profits just a few decades ago. But, of course, you live on the other side of the analytics revolution.

Through the EV looking glass, circa 2005

Looking back, there was as lot of money left sitting on the table in the 90s. In retrospect, everyone’s strategy about everything feels, well, suboptimal.

A series of things happened in the early 2000s—across sports, personal finance, politics, and information sharing—that moved the concepts and practice of EV maximization into mainstream chattering-class culture and behavior. Sports fans and TV commentators now talk intelligently about 4th down football decisions. Grocery stores use massive datasets to better understand their customers and position goods. Political campaigns rely on econometric analysis and the results of experiments to hone their GOTV spending. And consumers use the internet to comparison shop everything from investments funds to milk.

If we could somehow blast someone from 1985 into our current culture, my guess is they would be stunned by how numerically analytical it has become. Seriously, go watch some Price is Right bidding from the early 80s. It’s insane.

It’d be silly, of course, to say that nobody was trying to quantitatively model the world to maximize EV back in the day. People, after all, have been trying to systematically beat the stock market and horse racing forever; they had to add a shot clock to college basketball in 1985 because +EV stalling strategies were ruining the ends of games. But systematic quantitative analysis had not spread into many walks of life, and certainly hadn’t crept into mainstream culture.

And it’s not like a switch flipped in 2005; the roots of this transformation go back at least to the 1970s. David Sklansky was laying the foundation for modern GTO poker with his groundbreaking Theory of Poker in 1978; Bill James and the SABRmetric folks began developing the theories and language of Moneyball at roughly the same time. Low-cost index funds appeared in the 70’s, followed by ETFs in the 90’s. And much of this was built on earlier economic and statistical theory, notably John Von Neumann’s 1944 Theory of Games and Economic Behavior.

But progress was slow. In the mid 90s, poker was still a game dominated by “feel” players who relied on deep experience, opponent-reading ability, and exploitative strategies weak opponents had no idea how to counter. Batting average, home runs, and RBIs still dominated both public and team assessments of baseball players. Virtually all football coaches, even at the highest levels, were using awful, risk-averse strategies for 4th down decisions, 2-pt conversion choices, and late-game clock management. To let an opponent score in the NFL in 1990 would have been almost unthinkable. To pay a left-tackle a massively higher salary than a running back would have seemed equally absurd.

Today, of course, it’s not. The dam broke sometime in the mid-2000s. Part of it was popular books, like Moneyball (2003) and Freakonomics (2005), that brought the theory and practice of abstract model-building, behavioral economics, and EV maximization to the public. Some of it was the poker boom, which flooded the game will money and, in turn, incentivized people to bring modern technology and analysis to improving strategies, which spilled over to other endeavors. Some of it was people like Nate Silver, transforming election analysis via systematic quantitative analysis of polling data. Nowadays it’s hard to think of a field where these sorts of analytical strategies haven’t been brought to bear.

The underlying catalyst was the internet, which allowed potential EV maximizers to connect, share information, and spread the philosophy and strategies. Suddenly, EV maximizing websites were everywhere: how to get the most value out of credit card sign-ups, frequent flyer and hotel loyalty accounts; how to use compounding coupons to do truly amazing things at CVS; how to win your NCAA basketball bracket; how to avoid massive fees for investing and just dump your money in low-cost index funds; and a million other things.

To successfully apply a Riverian mindset to a particular field always required basic math and analytical tools. And some of those—like the poker solvers—are indeed new. But many of them are just standard classical or Bayesian statistics, or even just logic, combined with a calculator. What was missing was the data, the capacity to collect it, and the knowledge of how to apply it. Now that we are awash in data and interconnected with the internet, we are going to live in a more-Riverian world. And in some sense, it’s a one-way door; the grocery store isn’t going to stop studying your purchases to target you with ads, and fast food restaurants aren’t going to get dumber at maximizing their offerings.

At the same time, internet gambling and pseudo-gambling exploded. First, it was the online poker boom and offshore sportsbooks. Then it was fantasy football, followed quickly by daily fantasy sports. Finally, the legalization of sports betting in a wide swath of the United States and the subsequent embrace of gambling by the major sports leagues—something unthinkable just two decades prior—meant every NFL broadcast would feature endless commercials for DraftKings, and every ESPN show would be plastered with betting lines. Sports has always been intertwined with gambling, but it has never been so in-your-face and at-your-fingertips as it is now.

Even for people who already had a Riverian mindset, like me and my friends, the cultural shift took things to a new level. When Virginia legalized online sports betting in early 2021, it was an absolute bonanza of +EV sign-up bonuses and promotional bets. Thousands of dollars of free money. Well, free +EV. My friends and I—only a few who were actual sports bettors—quickly put together a loose consortium to share information, spot the +EV plays, and make sure we all got the maximum amount of money down. It was the natural thing to do. But it was only natural because we had been conditioned by the EV world we lived in.5

On the Edge unconsciously captures this cultural moment almost perfectly. The stated through-line of the book is risk and the Riverian mindset, but an unstated theme is just how much of society has been transformed into fertile grounds for the application of analytics, and how much analytics have taken over in so many domains.

Just 25 years ago, Jessie May’s magnificent novel Shut Up and Deal brilliantly portrayed poker as it was in the 90s, the protagonist Mickey completely dismissive of the early analytic types (“Larry Sandtrap,” a thinly-disguised David Sklansky) and their standard deviations and fancy calculations about what hands to play from what position. To those us who were there, there’s now a certain nostalgia to Mickey. To younger players, born on this side of the EV explosion, he’s just a terrible player. We now live in the world of On the Edge.

I will occasionally try to short-circuit a lot of my relatives’ bullshit political claims by offering them real-money bets on their assertion; this is a very Riverian thing to do. It pretty starkly lays bare when people are saying thing they actually believe and when they are just parroting garbage they heard on MSNBC or Fox News or from their friends. I also think it’s something that I wouldn’t have done in the before-times, when EV had yet to take over the world so thoroughly.

But here’s the thing: people with the Village mindset toward risk hate being offered such bets. Part of it is that they, like everyone, enjoy being able to spout off nonsense about politics that they don’t really believe, and they don’t like being called on it. But there’s also an underlying moral objection to the monetary quantification of political beliefs, or any beliefs. As the Riverian mindset creeps into more and more real-world places of high power—be it business or politics—the collision against the Village mindset becomes increasingly high-stakes and nasty.

It’s all pretty low-stakes when it’s just poker and sports betting and calling out your relatives’ bullshit at Thanksgiving. It’s an entirely different issue when it’s a philosophy guiding some of the most powerful people and industries in the world, and perhaps the most important invention in human history. And that raises as question: is a Riverian mindset +EV for society at large?

Philosophy, Politics, and Power in the River

Part II of On the Edge looks at Riverians and risk in the real world. As it happens, Silicon Valley—and especially the world of venture capital—is ground zero for applied real-world Riverian thinking: make a ton of longshot bets on companies that have a small probability of a massive return on investment. You will mostly lose, but the EV will be incredible, because the odds are asymmetric. You’re downside is only your investment. But your upside—if you fund the next unicorn—might be 100x, 1000x, or more. And you’ll be providing wonders to the world. As Silver describes, VCs are the embodiment of the Riverian personality—competitive, risk-tolerant, and contrarian. All with a belief that what they are doing is optimizing society.

Silver’s analysis of Silicon Valley is sharp. Like most of the chapters in On The Edge, a huge volume of information is packed into the writing, as are a large number of diversions down interesting rabbit holes. The discussion of the difference in the nature of risk for venture capitalist and startup founders is particular insightful, but short explainers and analyses about autism among Riverians, survivorship bias, and VC discrimination against women founders are also thought-provoking.

The most interesting discussions, however, are the political ones. For the first time, we start to see the politics of upriver tech types, best illustrated by Marc Andreseesen’s 2023 Techno-Optimist Manifesto. Tech is going to make the world better. Free markets unleash technology. Embracing risk and variance are the key to success. At its core, it’s a 21st century version of classical liberalism, where competition produces the greater good—in markets, in ideas, and in politics.

This leaves it open, however, to traditional progressive and conservative critiques of classical liberalism, mainly that Riverian techno-optimism, like classical liberalism itself, is an ideology pretending to be value-neutral but actually deeply committed to a set of non-neutral values. The prioritization of the individual in society over the community. A belief in creative destruction that gives no credence to traditional institutions or the plight of those who take risks and lose. And the substitution of the market for any type of fixed morality. Expected value is god, risk is king.

As you might have surmised, Silicon Valley Techno-Optimists and Village Mindset types are going to clash on all sorts of political dimensions. They fundamentally disagree about government regulation, the role of experts vs. the role of market disrupters, and the value of individualism vs. community and group. More interesting, however, is Silver’s personal ambivalence about Silicon Valley. In the big picture, he’s supportive of the Techno-Optimist visions and principles. But he’s skeptical about whether VCs are actually the contrarian risk-taking disruptors they appear to be, when they actually at this point may be more reflective of entrenched power.

It is at this point that On the Edge turns both downriver and upriver, with chapters on the wild, unregulated world of crypto, and also chapters on the Effective Altruism and Rationalist movements in the more philosophical parts of the river. All of it is loosely told through the cautionary tale of perhaps the most extreme Riverian of all-time: Sam Bankman-Fried, the once-billionaire crypto wunderkind turned prison inmate, whose brief but spectacular career arc traversed both ends of The River ecosystem. His belief in expected value, cost-benefit analysis, and utilitarian philosophy was so strong that anything short of risking your livelihood—and maybe even your life—on +EV plays was probably too risk-averse for him.

Imagine I’m once again offering you a roll of the die. This time, you can take $25 million dollars, no questions asked. If you roll the die, anything besides a 6 gets you $100 billion dollars. But if a 6 comes up, you are shot dead on the spot. Most normal people would simply take the $25 million, perhaps citing the declining marginal utility of money and the avoidance of massive variance—being dead!—as sound reasons to turn down the arguably +EV play of rolling the die.

An Effective Altruist might want to investigate the good that could be done with $100B in their hands, and make inquiries into what happens to the money if she declines the offer (maybe it’s all spent on military weapons, yikes!). After a lot of math, they might choose to roll.

Sam Bankman-Fried would grab the fucking dice. No ones’ life is worth more than the good $83B in expected value can do for the world. Especially in the hands of an Effective Altruist with the self-confidence and ego of SBF.

Village-mindset types at this point might bristle at the very idea of quantifying the value of a human life. It seems so, well, cold and calculating. But in the Riverian mindset—and especially for the Effective Altruists—these calculations are at the heart of the improving society, reducing global poverty, and bringing rational policy toward solving any number of medium and large global problems.

And this is where the real divide between The River and The Village becomes evident. Effective Altruists are overwhelmingly educated, center-left liberals. On paper, they could easily be mistaken for Village mindset academics or mid-level government managers who strongly support the Democratic Party. But their River mindset gives them a completely different set of intellectual, cultural, and political commitments and attachments. For an Effective Altruist, partisanship as an identity makes little to no sense. For The Village, the EA crowd just seems like a bunch of nerdy weirdos.

The most basic forms of Effective Altruism—such as evaluating and ranking charities —has undoubtedly increased total global welfare, as donors direct giving away from high-overhead, low benefit charities (like Heifer International) or already-wealthy institutions (like Harvard) and toward ones with low cost-benefit ratios (like fighting malaria). But the underlying utilitarianism of the Riverian philosophical movements and the broadening of their scope into areas like futurism and transhumanism should give one pause. As Silver writes, discussing one bizarre rationalist view of a transhuman future, “Does this sound like utopia or dystopia?”

As with the first half of the book, Silver’s breadth and depth of coverage here is wild. Crypto, options trading, market bubbles, meme stocks, EA, Rationalism, prediction markets, utilitarianism, pricing life, the Kelly criterion, and more. Combining all of this information could have been a literary disaster. But the presentation is thoughtful and flows well, even as it sometimes feels like sensory overload. Many of the topics are told through narrative interviews mixed with 538-style explainers. The sheer number of characters who appear in the book is also impressive. Those accustomed to Silver’s short-form analysis-and-commentary writing will be surprised at how much reporting and how many interviews appear is in this book.6

That combination also creates some of the most vividly memorable moments of the book. Like when Silver is explaining prediction markets and discusses his trip to Manifest, a conference in which participants can create betting markets on anything, such as whether there will be an orgy at Manifest (there was). Silver later interviews a Rationalist who hadn’t participated in the orgy, but had created data visualization graphs of other sexual markets she had been involved in at Manifest.

The most surprising takeaway from On the Edge is how concerned Silver is about the direction of much of the world of The River. Those familiar with his recent public writing might think that the main villain of the book would be a Village-mindset risk-averse pseudo-expert type, maybe a partisan journalist or academic.

Instead, the recurring danger of the book is the one built directly into the River. What if a bunch of hyper-rational successful risk-takers don’t sum to a collective meta-rationality? And what happens when the game isn’t poker or startup funding, but a global existential threat?

p(doom): Quantifying Existential Variance

Imagine you are given one more chance to roll the die. This time, you can have our current world. Or you can roll. If you roll and you are successful, the world becomes better beyond the wildest dreams of anyone: abundance beyond measure, poverty eradicated, all disease cured, war extinguished. A legitimate utopia. But if you roll poorly, humanity goes extinct. And here’s the catch: we aren’t quite sure how many of the numbers on the die lead to each outcome. Do you want to roll?

This is the dilemma of Artificial Intelligence development. Many hardcore Riverians in Silicon Valley are confident that accelerationism—essentially Move Fast and Break Things applied to AI—is the proper course of action, consequences be damned. Roll the fucking dice. The +EV upside for society is just too great, even if there are significant risks.

Others are more or less dismissive of AI risk, and think the entire idea of p(doom)—that is, the probability that AI will destroy the world—as so trivial as to be laughable. Even many “doomers” who believe p(doom) is unacceptably high see the development of AI as more or less inevitable—the die is getting rolled—and thus focus efforts on minimizing danger.

Silver brings the characteristic Riverian analytical detachment to the issue at first, with interesting profiles of the AI optimist (Sam Altman and an anonymous person named Roon, both accelerationist of varying degrees) and pessimist (Eliezer Yudkowsky, a doomer maximalist) mentalities, a discussion of game theory and nuclear deterrence, and a excellent explainer on large-language models like ChatGPT.

The detachment feels a tad alarming, even as someone who doesn’t think twice about pricing human life. What is the probability that Sam Altman is a utilitarian lunatic like SBF, willing to risk the world for on a very narrow +EV bet of creating Utopia? We should probably figure that out.

But it turns out Silver is anything but detached about p(doom). He’s not a doomer—and he doesn’t want to stop AI development from proceeding—but he’s worried. In part because, holy fuck, it’s scary. But also because existential humanity risk tends to break the Riverian toolkit; it’s just really hard to quantify. A true lack of data tends to freeze up a Riverian faced with a big decision. We can’t even get a reliable bid-ask spread in a prediction market for p(doom).

We also don’t have a good grasp on just how powerful or important AI will become; as amazing as ChatGPT is, it’s quite obviously not currently an existential threat to anything. Nor do we have a sense of the coming politics of AI. The public may have little or no appetite for any AI risk, and the regulatory structure placed on development may be largely designed to reduce the variance, even if it costs a lot of potential EV.

On the Edge ends with a discussion of the incredible progress that has been made in the world in the last 300 years, as Enlightenment philosophy and classical liberal political ideologies set the stage for the Industrial Revolution. Billions of people have been lifted out of poverty; the gains in the last 30 years alone are eye-popping.

Silver views this as the product of long-term public policy that has encouraged and rewarded calculated risk-taking among citizens and communities. Indeed, roughly equal access for citizens to stable property rights and functioning markets are not the norm in history. We are incredibly lucky to live in an age where risk is incentivized and rewarded. Liberal capitalist democracy, properly aligned, might just be the GTO solution for human flourishing.

But there are growing signs of secular stagnation when you zoom out. Global GDP growth has peaked. The American and other advanced economies just aren’t growing like they used to. Innovation is very difficulty to measure, but a lot of smart people think it’s decelerating. Others are convinced that inequality—in America or globally—is responsible. The question is how you respond. Silver, unsurprisingly, is on the side of unleashing the incentives of risk. On balance, I probably am too.

My guess is that this book is going to be controversial with a lot of mainstream liberals. The Village overlaps significantly with elite center-left society, and Silver does not hold back in his criticism of their increasingly risk-averse approach to public policy. Liberals who have already grown increasingly skeptical of him in the last few years will probably read him as a cheerleader for the most extreme-version of techno-optimism, and pan the book as a matter of course. Which, of course, is a very Village way to build an opinion about an argument.

One question sure to come up is where are the losers? One difficulty in making any +EV bet is that you can only do it if there’s someone on the other side of it, willing to take what you know is the worst of it. Noticeably absent at times from On the Edge is a discussion of those on the other side of the bets, or how to think about them structurally. It doesn’t really matter at the poker table, but if we want to encourage calculated risk-taking for the benefit of society, we need an account of what happens to the people who go for it and fail. And if we aren’t willing to cushion their landing, we are probably incentivizing too much risk-averse behavior.

I’m also skeptical that The River and the The Village are locked in a battle for control of America’s future. For one, the distinction is a bit overstated. Like Silver, I have spent a lot of time in both worlds and I can vouch for the basic accuracy of his depiction of them. But there’s also a lot of overlap and messiness. Hardcore academics who think in marginal effects and make jokes about their priors. Poker players who are radical risk-averse socialists away from the table.

But more importantly, the equilibrium for maximizing human flourishing might depend on the existence of both The River and the Village, and a balance between their political influence. We avoid revolutions, left or right, because our stable political institutions allow us to create massive wealth but also create child labor laws, a progressive income tax, and social insurance systems for the elderly. Silver posits that was we need a compromise between The River and the Village over the basic terms of our future. But that suggests things might be further off the rails than perhaps they actually are. Maybe we just need to let them keep competing.

On the Edge is a rollicking good time of a read, thought-provoking and informative throughout. It is, by far, the best book I’ve read this year. Do the +EV thing and get yourself a copy of it.

When I was 17, almost everyone I knew was like this. My family. My friends. My girlfriend’s family. Her friends. Everyone wasn’t quite as extreme was we were, but they were some version of it. I just assumed that’s what the whole world was like. Turns out it was selection bias. There are people out there who don’t play games. Or play, but don’t think about the strategy, or ever talk about it. People who literally don’t keep score when they go play mini-golf. I just wasn’t in their world, and they weren’t in mine.

This is exactly how all insurance works. You pay a modest amount of money in order to avoid the worst possible outcomes. It’s a negative EV proposition and you are happily taking it to reduce your variance. The only way for the insurance company to make money is to charge more than, on average, than they will pay out in claims. Your expected value is highest to just roll the dice and hope you don’t get cancer in your 20s. But by taking a mildly -EV option—buying a cheap health insurance plan that in all-likelihood you will never use for a big hospital visit—you can avoid the nasty downside of the unlikely $150,000 bill if you need cancer treatment when you are 23.

The first time I got called a degenerate I was in 6th grade. My friend Jeff and I were in his driveway, playing HORSE for $1/letter. His dad—an Italian-American with a Brooklyn accent straight out of central casting—came out of the garage, took one look at what we were doing, and said “you two are going to be the youngest degenerates in history” as he walked toward the backyard. I had never heard the word before, and I was sure it a negative comment. But I also detected some begrudging pride in his voice.

When people play casino games against the house, they are doing something like the opposite of the variance-reduction play. They are taking a -EV option with the hopes of hitting the unlikely outcome. This is part of the reason why casinos are both popular among people and profitable for the casino. They offer a -EV wager with a very wide variance. A pull on a slot machine has an expected value of something like -8%, meaning you get back 92 cents for every dollar you put in.

It would be supremely stupid for casinos to just payout the exact EV of the slot machines. Imagine putting a dollar in, pulling the lever, and having 92 cents splash out the bottom every time? Nobody would play. Instead, the games are structured so that most of the time, you get nothing when you spin the lever, but once in a while, a whole bunch of money falls out. Same EV, different variance. The precise schedule upon which slot machines pay out, has been studied extensively by casinos and set at the point that maximizes the most revenue.

An open question we often discussed was whether spending hundreds of millions of dollars of marketing money on these promotional bets was +EV for the online sportsbooks. It might have been—either via gathering customers who would ultimately lose money, or by beating out market competition from other sportsbooks—but they were spending an awful lot of money. Sometimes there’d be an individual bet promotion, lasting one day, that would cost them tens of millions of dollars in EV.

Full disclosure: even *I* make a brief appearance. Somehow I found myself across the table from Silver at a beachside bar at the luxury Baha Mar resort in the Bahamas in 2023. I was there because I had won a writing contest that got me a free-entry into a $25,000-entry poker tournament, something I would normally have no business playing in or, for that matter, going anywhere near. Silver was there because, well, lots of people like me were there, a +EV opportunity way too good for any credible degenerate to pass up.

This is one of the best book reviews I have ever read. It does a great job of explaining Silver’s unique insight into many subjects - I believe a key litmus test for people is whether they appreciate what he has to offer. I am definitely more of a Villager, not down with accelerationists etc., but I am routinely wowed by what he has to say. Looking forward to the book!

I’d already preordered the book, but this review made me much more confident I’ll enjoy it! Well-written.