The 119th Congress officially begins at noon on Friday. For the second Congress in a row, we are faced with the prospect of a contested Speakership election at the outset of the Congress. Below are (1) some background materials on the procedures and politics of Speakership elections; and (2) an assessment of some of the political dynamics of the election and its effect on the rest of the 119th Congress.

Background Materials on Procedure/Politics

If you want to do some light background reading about the procedural features of a beginning-of-Congress Speakership election, I recommend my Notes for Talking to Reporters About Speakership Elections, which was produced as a quick-reference document prior to the 118th Speakership contest. It’s not an authoritative procedural guide, but I think it is a very good primer.

I also published an academic retrospective of the January 2023 election that is a very detailed—but pretty accessible, IMO—procedural and political review of the contest, including a more rigorous and footnote-heavy review of the procedures. True sickos can also look back at my Twitter timeline for the January and October Speakership contests.

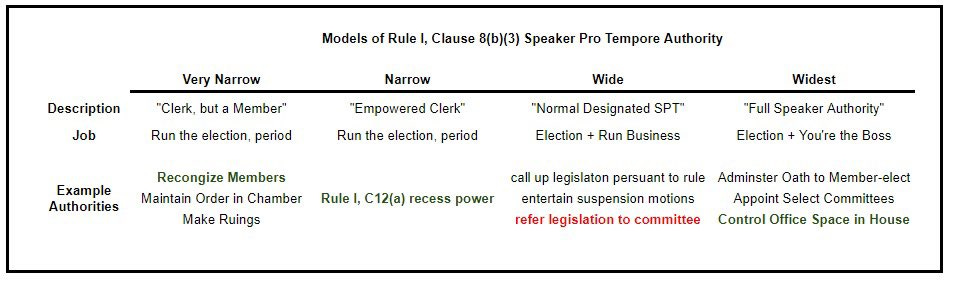

Note that the October 2023 Speakership contest (ultimately won by current Speaker Johnson) was a somewhat different beast, both procedurally and politically, because it occurred in the middle of a Congress, after the House had been organized for 9 months. That meant that it was conducted under the adopted 118th House rules (rather than General Parliamentary Law) and presided over by the Rule 1, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker Pro Tempore (SPT), Representative McHenry, rather than the Clerk. This also provided SPT McHenry with some tools not available to the Clerk, such as the Rule 1, Clause 12(a) authority to recess the House subject to the call of the Chair.

Nevertheless, a fair amount of the politics of the October 2023 Speakership contest is still relevant to the current election. I previewed the procedures and politics of the contest in the week between the passage of the resolution vacating the chair and the first ballot, and I think my Game Theory of the Republican Speakership Crisis (written during the contest) still holds up as a general analysis of the political dynamics. Late in the contest, I outlined the political problems with the GOP conference rules, and did a general piece discussing the late-game politics of the contest. Less relevant but possible of interest are an explainer on the procedures for the so-called Motion to Vacate and an early foray into the powers of the Rule 1, Clause 8(b)(3) SPT.

Some Political dynamics of the 119th Speakership Election

We may not even have a contested election on the floor Friday. One thing largely overlooked during the runup to the 118th fight is that virtually all would-be Speakers bargain with their caucus/conference over rules, committee slots, agendas, and specific policies. In some sense, that’s what the Speakership election is—a party collectively deciding power and agenda dynamics among its factions. Most of the time, the Speaker-nominee successfully accomplishes this in November/December, People forget, but Pelosi had to explicitly do this in the leadup to the 116th Congress, when a faction of Democrats holding the balance of power wrote a letter threatening not to vote for her. She had to buy them up, but did so long before the voting began. McCarthy wasn’t able to do that in 2023.

We aren’t starting fresh here. Johnson is already Speaker, and has already behaved in ways that anger his right flank. He already has cut deals with the White House, the Senate, and the House Democrats. He cut appropriations deals. He cut foreign aid deals. He cut CR deals. Everyone has their eyes wide-open; they know Johnson is going to cut deals that box out the uncompromising right wing not just because that’s what legislative leaders have to do. It’s because he’s already done it repeatedly.

Johnson has plenty of GOP conference Members red-hot. Massie says he’s not voting for him. Chip Roy looked ready to flip the entire chess board during the CR fight. And a handful of Freedom Caucus types are publicly on the fence.

One distinction between Johnson and McCarthy is that no one has it out for Johnson the way Gaetz had it out for McCarthy. Sometimes it’s not whether you have the votes or not, it’s whether someone is organizing the votes against you. That’s a plus for Johnson.

Here’s a quick procedural review of the Speakership election for those who skipped the great reading above. The House Rules have not yet been adopted, so the Clerk of the House is the presiding officer under law and custom, and the chamber operates under the General Parliamentary Law. The parties have already nominated Johnson and Jeffries, but any Member-elect may also nominate anyone from the floor. The vote is conducted viva voce with an alphabetical call of the roll. Members may answer with a name (nominated or not) or say “present.” They are not required to vote. You do not need an outright majority of the House to win; instead, you need a majority of the total votes cast for a named person. If no one has a majority, the Clerk immediately proceeds to a second ballot, but Members-elect may seek recognition and gain the floor for motions or unanimous consent requests. The motions/UCs can be for a variety of House actions, including adjournment and the offering of resolutions to alter the election procedure or have the House do other things. Members-elect can raise points of order, the Clerk can rule on them, and Members-elect can generally appeal those rulings. In January 2023, each vote for Speaker took about 80-90 minutes, and the House voted between two and five times each day, before adjourning for off-floor politics and negotiation.

The math right now is brutal for Johnson, or any Republican. The House will be 219-215 on Friday (recall Representative Gaetz resigned). All 215 Democrats will support Jeffries for Speaker. The general formula for votes needed to win is as follows: one more vote than the second highest vote-getter, and then an absolute majority of the total number of remaining Members-elect, with affirmative votes counting as 1 vote, and non-votes (or “present” votes) counting as 0.5 votes. For example, with the expected 434 Members-elect, if candidate B (Jeffries) has 215 votes, candidate A (Johnson) would need 216 votes, plus 1.5 total “votes or non-votes” from the remaining 3 Members-elect. This could be accomplished, for example by getting all 3 to vote present, or by getting 1 to vote for candidate A and 1 to present, or by getting 2 to vote for candidate A. If just two Republicans vote for another named candidate, Johnson cannot get a majority.

The Democrats aren’t saving Johnson this time. Democratic Leader Jeffries already announced that. Back during/after the Foreign Aid deal, there was some talk on the right-wing of removing Johnson, and Jeffries let it be known that the Democrats would not sit on their hands like they did when McCarthy was removed; instead, they would vote to sustain him. This time, he’s going to need a partisan majority to remain Speaker.

That’s honestly the only way to do it. As I’ve said many times, the Speakership isn’t a prize you win, it’s a coalition you lead. It’s not just one vote, one time. As I wrote last October:

You need to create a stable procedural majority such that you can Consequently, anyone looking to be Speaker—McCarthy, Scalise, Jordan,, or otherwise—needs to not only find a way to win a majority on the floor during the election of the Speaker, but also needs to secure a party settlement that brings the various factions into an ongoing procedural coalition. Absent the creation of that stable coalition, every vote on a special rule to bring legislation to the floor is a potential failure. And that’s because every procedural vote in the House is essentially a revote on the Speakership. If the procedural coalition collapses, the Speakership collapses. If Democrats had helped McCarthy win the Speakership in January—perhaps by voting present, as many observers suggested they could do in exchange for some goodies—it might have won him the office, but it would have left him in the exact same bind on the very next vote. Unless he was willing to create a permanent procedural majority coalition with the Democrats, there was no point in getting their help that one time. His only choice was to try to make peace with the GOP rebels. Ditto on the resolution to vacate the Speakership.

Now, there was arguably no stable procedural majority in the 118th House. McCarthy gained the Speakership on a tenuous bargain with the right-wingers, and their support was withdrawn as soon as he cut the budget deal in the spring. They then proceeded to deny the leadership a procedural majority, repeatedly blocking bills from coming to the floor. McCarthy and Johnson both had to resort to using the suspension process—and thus necessarily bargaining with Democrats—to set the agenda and move the must-pass legislation.

In some sense, we can already say there won’t be a stable partisan procedural coalition in the 119th. We know this because it seems impossible that the minimum demand of the right-wingers won’t be to keep their seats on the House Rules Committee, which will once again give them a veto over brining legislation to the floor via a partisan special rule. The Speaker has been in almost total control of the Rules committee since 1963. I assume when a party gets stronger control of the House, we will revert to that arrangement. But for now, it may be better to think of the House as a coalition government, and maybe even a three-party system.

None of that seems the same to me as saying that Johnson could effectively run the House if he used Democratic votes to secure the Speakership. Even if the House is a coalition government, it’s a coalition of two parties that are mostly in line with each other. To use Democratic votes to try to win the election would probably drive away more Republicans, and open up a larger chasm of dissenters on the right going forward. Unless Johnson was truly trying to create a new, cross-partisan majority in the center, it would almost have to collapse. He’s not trying to do that, and so he can’t go that direction.

Trump is an known-unknown. He’s playing coy right now, but he almost certainly holds the balance of power. If he comes out strong for Johnson, it’s probably enough to shut off dissent and maybe even get the job done on the first ballot. He was able to shut off a potential symbolic revolt in the conference nominating meeting in November by strongly backing Johnson. Likewise, if he publicly and forcefully bails on Johnson, he’s probably sunk.

That said, Trump is a kingmaker but not a dictator. He could make or break Johnson, and I think he could probably demand and get Emmer or Scalise, but I don’t think he can simply install whoever he wants. Just like we saw with the Gaetz nomination for Attorney General and his push to get the debt limit wrapped up in the CR, his juice in Congress is often badly overstated by a lot of people. If he supported Marjorie Taylor-Greene for Speaker, for instance, I’m sure it would flounder. I’m not even confident he could get Jim Jordan over the top, although that would be closer.

The Electoral College vote count may focus the process. The Speaker election will begin on Friday, and looming on Monday is the counting of the electoral votes. I don’t think Trump has any interest in messing with the count. And so there’s going to be a lot of pressure to coordinate on someone without a protracted fight. It plausible that the House could hold a joint session and count the electoral college votes without a Speaker, but it would be procedurally complicated, totally untested, and potentially raises Constitutional questions. There’s no doubt that everyone would like to avoid that, and particularly president-elect Trump.

By the way, if there is a floor fight for the Speakership, there are plenty of easy and legitimate work-arounds to count the votes before settling on a permanent speaker. The easiest and most Constitutionally-bulletproof solution would be to elect a Speaker, with everyone in agreement that person would step down after the counting of the electoral college votes. Their only job would be to preside over the swearing-in of Members, the adoption of temporary House rules, the passage of a concurrent resolution to count the electoral college votes, and the actual counting of those votes. After that, the person would step down upon the election of a successor, and the real Speakership election would continue, under House Rules and with the temporary Speaker presiding (similar to the October 2023 election). This solution is so easy and so obvious that I expect it to be implemented if there really is an unlikely deadlock over the weekend. And I hope the caretaker Speaker would be Tom Cole.

Great piece! Kind of random, but once it became clear that Democrats won 215 House seats, I started to wonder if they could band together with a few moderate GOP members to elevate Fitzpatrick or Bacon to the speakership. I get all the challenges in even trying that, but do you think it wasn't fully explored?

Is the deal concerning raising the Motion to Vacate threshold from one vote to nine votes still a part of the proposed rules package for next Congress?

If it is, Johnson can breathe a lot easier once he's sworn in. But I think that even with Vice President Trump’s endorsement (which President Musk immediately undercut by publicly trashing Johnson, and which Massie among others openly laughed at) that’s got to be one of the things the hardliners try to get dropped before they give him the Speaker's gavel again.