Should the GOP conference change its rules?

Procedures are important, but substance drives opinion

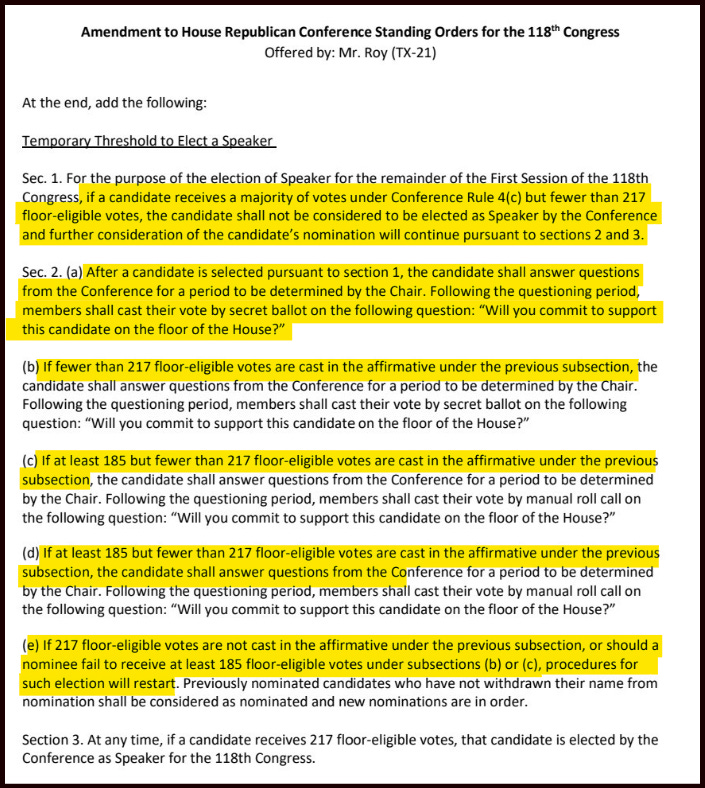

The House GOP conference is holding an election today to nominate a candidate for the Speakership. Here are the current rules of procedure for the election, which come from the conference rules for the 118th Congress:

There are three important features to these procedures:

It’s a secret ballot

There are nominating speeches, but no discussion

You need a majority to win; if there are multiple candidates and no one has a majority, you have repeated runoffs with the lowest vote-getter dropped off.

This system, or something similar to it, has been in place in both parties for quite a long time, in part because it works pretty well. There is, however, one flaw. For all party offices except Speaker (majority leader, whip, conference chair, etc.), this is the entire election. Get a majority and get the job. The Speaker, however, is elected on the floor by the full House, since it’s actauly not a party office but a constitutional one.1

That creates the now well-known problem that you only need a majority of the vote in your caucus/conference to get the party nomination, but you need a much larger proportion of the party to support you on the floor to win the Speakership, since you aren’t going to get any vote from the minority party. Under current rules, 111 votes will be good enough to win the GOP nomination today, but 217 votes will be needed to win the Speakership on the floor (both numbers assume full voter participation). Since the GOP conference has a narrow 221-212 majority in the House, you need almost every Republican to vote for you in the House floor election, but you can get the nomination even if 100 people vote against you in the conference.

This was never much of a problem in the past, because norms of party loyalty— combined with strong threats of punishment from the leadership for defecting on the floor—kept party members in line. Even when the Democratic party was hopelessly divided in the 20th century between northern and southern factions that disagreed ferociously on social issues and particularly civil rights, they never had a problem electing a Speaker. Ditto with the Republicans. You vote for who you want in the caucus/conference, and then you support the party nominee on the floor. Simple as that.

Those days are gone. Defections on the floor for the Speakership vote have increased dramatically, in both parties, since 2011 (chart via @mattngreen):

And obviously, we saw all this in action during the Speakership contest in January 2023. Former Speaker McCarthy won the Republican nomination 188-31 in the conference. But it took 15 ballots on the floor, because 20 or so Republicans refused to vote for him until he made concessions on policy, rules, and committee assignments.

Do the traditional conference rules still make sense?

Now the Republicans are back in a conference preparing to nominate a new candidate for Speaker. Two candidates—Majority Leader Steve Scalise and Judiciary Committee Chair Jim Jordan—are the frontrunners. But no one believes either of them are going to get 217 votes in the conference under the current procedures. Instead, what you will have is someone getting a majority and thus the nomination—the current rules with their runoff procedures guarantee you a majority winner—but not necessarily the pledged support of the enough votes to win on the floor on the first ballot.

This has as lot of people thinking that maybe it’s time to change the conference rules, at least temporarily, to require 217 vote for the nomination. Such a change would have a bunch of advantages for the party:

It would allow the party to unify on a Speaker during the conference, prior to going to floor. The current rules short-circuit the process of uniting the party, because they end the nomination process well short of the necessary floor votes.

That saves you a messy floor fight in public, which is probably good for the party. You can have it out behind closed-doors, and then come forward as a unified conference.

In this particular instance of a mid-Congress election, it also recognizes how short we are on time. Normally, the patty nominee is chosen in November and the floor election is in January, allowing the nominee about 6 weeks to sew up any missing support. This week, we’re talking about a matter of hours or days.

But there are disadvantages as well:

It doesn’t guarantee a winner. The current rules get you a nominee. A 217 rule in the conference means you could deadlock there, just like on the floor in January. Pushing the floor fight into the conference could make for a very long conference.

It might embolden factions. It’s pretty obvious by now that any group of 5 hell-bent dissenters can deny the Republicans 217 on the floor. But so far, only the Freedom Caucus crowd has been willing to do that. Would more groups enter that fray behind closed doors in the conference, without the prying eyes of the public? I think it’s definitely possible.

It’s a secret ballot. On the floor, at least you know who the dissenters are. In the conference, you wouldn’t even necessarily know who you were bargaining with, as people could pretend they were on-board with the party but keeping voting in dissent, in order to exhaust the conference in hopes of new candidates emerging.

Enter Chip Roy’s proposal

A few days ago, 94 House Republicans signed a letter indicating they were interested in changing the conference rules to some form of 217 voting. And last night, Chip Roy put forward a specific proposal to amend the conference rules:

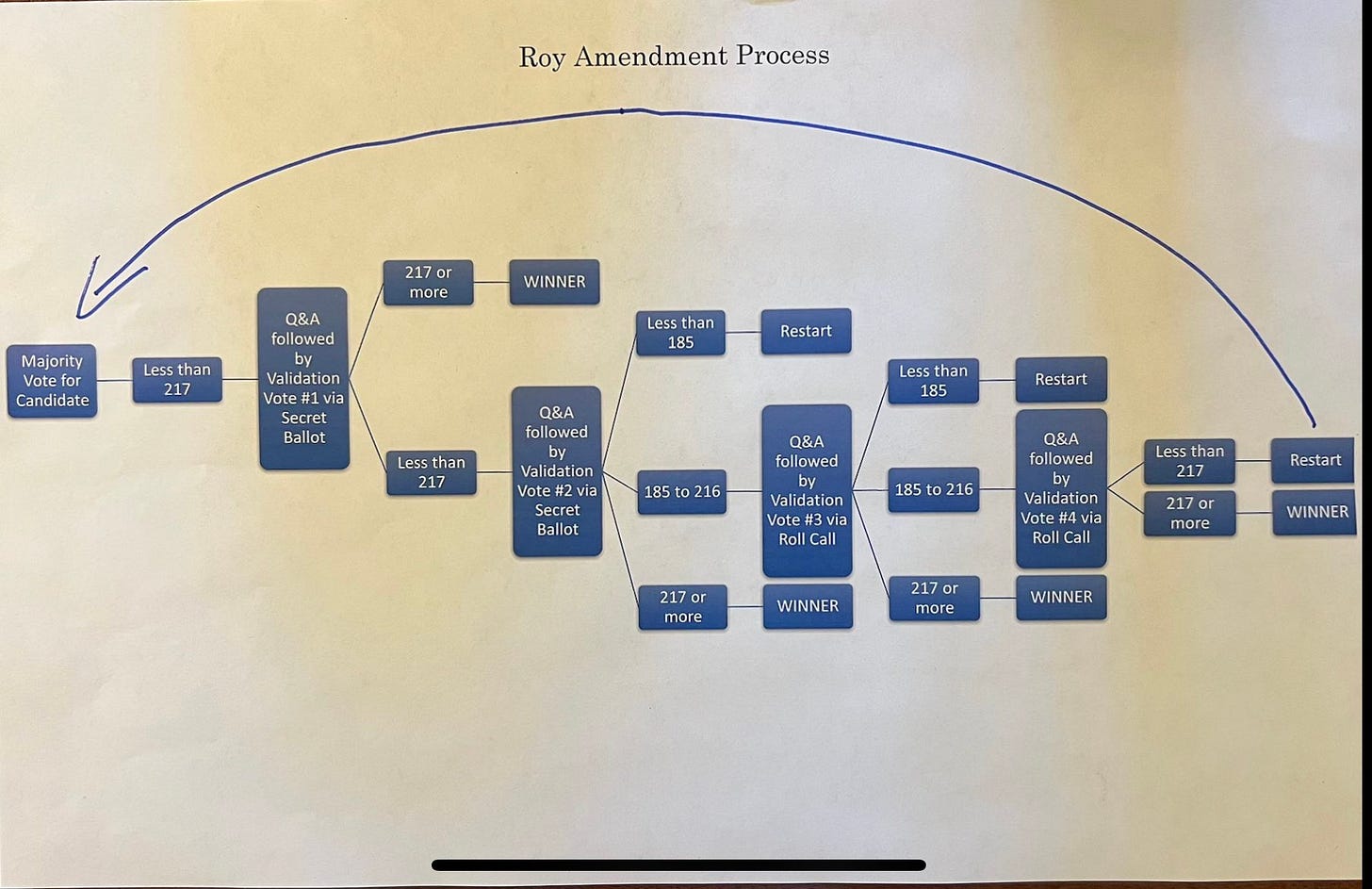

The basic outline is this:

Normal procedures to get a initial proto-nominee under current conference rules;

If the proto-nominee doesn’t have 217 votes, they answer questions from the conference, and then there’s an up/down approval vote on the proto-nominee;

If they don’t get 217 in the first approval vote, another question period and a second approval vote;

If they don’t get 185 in the second approval vote, the whole thing starts over. If they get 185 but not 217, then another question period and then a third approval vote, this time by non-secret call of the roll.

If they don’t get 185 in the third approval vote, then the whole things starts over. if they get 185 but not 217, then another question period and then a fourth approval vote, also by no-secret call of the roll.

If they don’t get 217 in the fourth approval vote, start the whole thing over.

Here’s a great visual of the process, courtesy of Emily Brooks from the Hill:

As far as 217 plans go, I think this one is…ok. I like how it tries to force the conference to confront itself, via the questioning period and then, eventually, the public roll call vote. I can see how both of those pieces would serve to build unity in the conference, by allowing the proto-nominee to work to build support and also to let everyone see the holdouts so they can isolated and pressured.

That said, it’s a little clumsy. Part of the way you get holdouts to give in is to offer them side deals, in private negotiation. This feels more like it’s setup as a church basement meeting, where everyone knows everyone’s business. That might not be conducive to getting to 217 when you are down to 6-10 holdouts, many of whom might like to be bought up but don’t want to be publicly airing those negotiations.

Obviously, side deals could be worked out as this process is going on, but it’s not obvious to me that there’s any real point to the question and answer period, which could create divisions just as easily as it could create unity. And the public roll call votes could really bog down the time each round takes, exacerbating an already long process that has no forced endpoint.

There’s definitely something to “get everyone in a room and don’t let them leave till it’s solved,” but 8 determined people might be able to wear down a majority faster than a majority can wear down them. What happens when this thing goes three full cycles (15 votes!) and you are still stuck?

None of these normative discussions matter

Whatever the merits of everything I’ve said above—or any better arguments you could come up with2—that’s not how the party is going to go about deciding whether to change the rules. And that’s because a rules change like this has both (1) value to the party as a whole, but also (2) strategic implications for the candidates and their supporting factions.

The normative arguments for this sort of change are mostly about what is good for the party. But for any individual candidate—or any Member who strongly prefers one a particular candidate—the rules change is going to be viewed through the lens of how it affects the substantive outcome of the election. And that’s pretty straightforward:

If you believe you are going to be the party nominee under the current system, you probably don’t want to change the rules; getting the nomination with a majority doesn’t guarantee you success on the floor, but it makes you by far the most likely person to end up Speaker. Yes, it may be a slog on the floor and no, that’s not great for the party, and yes you could end up losing, but by becoming the nominee you will pick up a ton of support from people who didn’t vote for you but don’t feel strongly about it, and you will be able to put pressure on others by appealing to party loyalty, and in the end you’ll maybe have to buy up some votes or go multiple rounds on the floor. But maybe not!. If you have 111+ votes in the conference and you know it, changing the rules isn’t in your interest.

If you believe someone else has a majority in the conference, you probably want to get the rules changed. For the opposite of all the reasons above. Once you go to the floor with someone else, there’s going to be immense pressure on you to back them and try to end this thing; in the conference, that pressure will be reduced and the opportunity to prove they don’t have 217 will allow you to make the case that you should be the nominee. Lots of fence-sitters will jump onto the nominee, but fewer than would if you were heading to the floor. And what do you have to lose? You almost certainly aren’t going to be Speaker if you don’t change the rules.

If you are a secret dark horse candidate, you want the rules change. Your best hope is deadlock that exhausts people, and even better one that proves neither of the top candidates are going to have an easy time uniting the conference.

The bottom line is that anyone with a conference majority knows they will probably end up Speaker, though it may be a slog of negotiations and multiple ballots on the floor. Anyone without a conference majority knows they will likely not.

And this is largely what I think we are seeing from the candidates. Majority leaders Scalise is against changing the rules, and this is almost certainly not out of any normative view of what is best for the party, but simply because he thinks he has 111 votes. So he’s going to run a line that people should just support the party and fall in line with whoever wins.

Conversely, the Jordan crowd seems to think it doesn’t have the majority. And so they (along, apparently with some McCarthy folks) are pushing for the rules change. Again, it may or may not be good for the party, but it certainly is better for someone who wants to win but doesn’t think they have a conference majority.

The strong supporters of each of these factions will largely fall in line behind the rule change position that comports with their substantive views. The question is what will Members do who don’t strongly support either candidate? They will be much more likely to weigh the normative consideration about the good of the party, balancing that with their candidate preference.

Article 1, section 2, Clause 5 states “The House shall chuse their Speaker and other Officers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment.

Which are probably substantial, I’m writing this at 6am.