Notes from a quiet week in the House

A lot can happen when nothing is happening

Almost nothing has happened on the floor of the House since the Office of the Speaker was vacated when the House agreed (216-210) to House Resolution 757 at 4:45pm last Tuesday.1 When the House is called to order tomorrow (Tuesday, October 11) at 11am, it will have been almost a full week without any substantive legislative activity on the floor.

A lot can happen in the House in a week where nothing happens, evidently. Here are some assorted notes on what I saw last week and how I’m thinking about this week.

Powers of the Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker Pro Tempore

1) We have a lot of developments in the ongoing saga of How much power does Speaker pro tempore McHenry have? The political consensus on both sides of the aisle has settled on “very little.” Strong evidence has been unearthed (originally by Rep. Jim McGovern, ranking member of Rules) that the original design of of Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) in 2003 intended a very weak, Clerk-like Speaker pro tempore, whose authority would be for the “sole purpose of electing a new Speaker.”

2) Large segments of both parties have largely accepted this reading of the rule, and that’s a reflection of the short-term politics, I think. For the Republicans, a very weak Speak pro tempore simply marking time until the election precludes any substantive legislation coming to the floor that might further divide the party or upend the election. The GOP is more than happy to suspend substantive floor fights until after the election. And I think McHenry’s decision to remove Pelosi and Hoyer from their Capitol hideaways under Rule I, Clause 3 authority specifically drove Dems toward the weak-reading of the Speaker pro tempore power.

3) While I accept that the very narrow view of the Speaker pro tempore powers is the original intent as well as the now accepted read of the contemporary House, I think this is a normative mistake. It simply does not make sense to me to have a Speaker pro tempore that exists for the purpose of continuity of government in an emergency situation, but make them no more powerful than the Clerk.

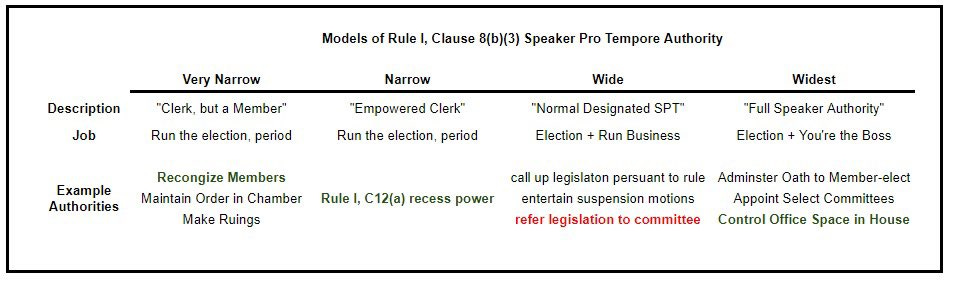

We have two other models of Speaker pro tempore in the House rules/practice—the elected Speaker pro tempore (who is nearly as powerful as the elected Speaker) and the designated Speaker pro tempore (who also has nearly full legislative authority)—and making the Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker pro tempore have powers roughly in line with either of those models seems totally appropriate.2 I would urge the House to reconsider this after all the dust settles. I made this chart to think through four different levels of authority we might want McHenry to have, just to guide thinking on the issue.

4) Despite the agreement on narrow authority for the SPT, McHenry has still had to make all sorts of decisions that will set the original soft precedents for future Members who assume the role (maybe sooner than you think!). By my count, McHenry has done the following things: recognized a Member on the floor, examined and approved the journal, made a unanimous consent request from the chair, refused to refer bills to committees, recessed the House under Rule I, Clause 12(a) authority, and rearranged office space under Rule I, Clause 3 authority. He has also been granted a significant security detail. 3

5) Whatever the powers of McHenry in the current scenario, I think a lot of people have confused the power of the SPT with the power of the House. Some people have gone as far as to suggest the House might not be able to pass a resolution absent a Speaker, and a lot more people are saying things like “the House is paralyzed without a Speaker.” I think this is all, for lack of a better word, nonsense. It confuses the authority of McHenry under the House rules with the authority of the House under the Constitution.

In my view, the House has full-authority to act, even in the absence of a Speaker or Speaker pro tempore, under its plenary power as a legislature. The Speaker has no constitutional authority; the House could make them a virtually powerless figurehead under its rules (as the Senate has largely done with its president). And the House can already, under its contemporary rules, take up and pass legislation without the Speaker needing to use any authority beyond the presiding authority of a clerk. But as a bottom line, there is simply no reasonable debate about whether the House could elect McHenry SPT for a handful of hours and then do whatever it wants. This indicates that the House is not paralyzed; it is simply choosing not to act right now (which is totally fine!).

The Speakership Election: A Field Guide

6) We do not have an exact date or time for the Speakership election in the House. The House meets at 11am tomorrow, but almost certainly won’t proceed to the election at that point; Speaker pro tempore McHenry has indicated that he would like the parties to conduct their candidate forums by today or tomorrow, and the GOP nomination vote looks like it will initially (see below) take place on Wednesday morning. That would potentially setup the Speaker election in the House for as early as Wednesday afternoon. But there’s no deadline for the House to conduct the election, and lots of scenarios in which the GOP might prefer to delay it.

7) How things go in the Republican conference this week will go a long way to determining what the election looks like on the House floor. One question that has been raised by some Republicans is whether the conference should change its rules for nomination. Currently, only a majority of the conference is needed to win the nomination. But 94 GOP House members signed a letter seeking to change the conference rules and raise the threshold for nomination. It looks like this potential change might come up at the GOP meeting today.

In my view, changing this rule might be a good idea for the GOP. There’s always been a tension in the House between the party nominations for Speaker only requiring a majority vote, but the election on the House floor essentially requiring almost the entire party to back the candidate (since the whole House votes and the minority party isn’t going to help you). For over a century, this was simply enforced through party norms and discipline. Even if your candidate lost in the conference vote, you supported the party nominee on the floor.

That norm has plainly broken down in recent decades, with more and more party members defecting on the Speakership vote, in both parties. And obviously the Freedom Caucus went all the way in January and fought the party nominee for 15 ballots. So even though McCarthy won the party nomination 188-31 last November, it didn’t end the fight. Heck, it didn’t even address it. Raising the threshold for nomination—perhaps all the way to 217 (the current House majority number)—could move the messy floor fight into the party conference process, which has the advantages of (1) not going to the floor until the fight is over; and (2) not having the fight in public. I think this makes particular sense for a mid-Congress election, where there’s not going to be a lot of time between party nomination and floor contest. 4

8) Also looming is a potential fight over changing the House rules in regard to the so-called motion to vacate. Currently, a resolution to vacate the Office of the Speaker is privileged and can be raised unilaterally by any Member and offered as a Question of Privilege from the House floor. This is what Rep. Gaetz did last week. That rule, however, is new this Congress. During the 117th Congress, Rule IX, Clause 2(a)(3) made such resolutions privileged only if offered by direction of a party caucus or conference, effectively neutering it as a factional weapon. One option would be to return to this rule. A myriad of other possibilities exist, from raising to the threshold to something higher than 1 but lower than a majority of the caucus, to shifting over to a system of an expedited discharge petition for vacating the Office of Speakership.

One weird dynamic to all of this is that any individual Member’s position on the so-called motion to vacate is going to largely be instrumental to their substantive position on who should have the Speakership. Everyone wants it to be impossible to remove their guy from office, but easy to get rid of someone they don’t like. Similarly, every candidate for the Speakership is personally going to be against the making it easy to get rid of the Speaker!

9) How things go in the GOP conference is going to directly impact the structure of events on the floor. If the conference can rally around a single candidate who is likely to win on the first ballot, the floor will be a pro forma ceremonial event, probably done by resolution and without much drama. Ditto if the conference vote is something like 195-27 and the party can compel the loyalty norm to hold with appeals to going along to get along and agreements on rules and protocol changes. But if deep divisions persists—a 120-102 nomination victory under the old majority rule or a 200-22 victory with no settlement and the dissenters ready to fight on the floor—we could see a repeat of January, conducted under similar, but different, rules and structure.

10) There have been 10 previous intrasession Speaker elections in American history. Four Speakers died in Office5 (Kerr, 1876; Rainey, 1934; Byrns 1936; Bankhead 1940; and Rayburn 1961) and six have resigned (Clay 1814; Clay 1820; Stevenson, 1834; Colfax 1869; Wright 1989; and Boehner 2015). In three of the resignations (Colfax, Wright, and Boehner), the Speaker resigned effective upon the election of a replacement, so there was no vacancy in the Office.

11) Only two of the intrasession elections have been contested beyond a first ballot, both prior to the civil war. It took 22 ballots in 1820 to elect Speaker Taylor, and 10 ballots in 1834 to elect Speaker Bell. There were multiple candidates in 1814, 1876, 1962, 1989, and 2015, but each ended with a candidates securing a majority on the first ballot. In 1868, 1936, and 1940, no one challenged the presumed Speaker, and motions/resolutions were adopted on voice votes.

12) The mechanics of the Speaker election will be similar to the mechanics outlined in my lengthy note from December about the January election. (Some of that information is repeated here). The election itself can be conducted by any number of means. Past elections have been done by (1) viva voce vote in response to the call of the roll, (2) by ballot, and (3) by resolution. Any are acceptable, and it is up to the House to choose its method of election. The beginning-of-Congress Speaker vote has been done viva voce since 1839. Prior to 1839 it was done by ballot. The intrasession elections have been done by ballot (1814, 1820, 1834), by viva voce vote (1876, 1962, 1989, 2015), by motion (1868), and by resolution (1936, 1940).

I suspect that the manner of voting may partially depend on the political situation. If there is an open contest in the GOP when it goes to the floor, I suspect we will see viva voce calls of the roll, as we did in January. If there is going to be a clear first-ballot winner for the GOP, on the other hand, you might see a resolution offered and an up/down vote on a single candidate. One thing to remember is that you can’t use the electronic voting system for an open field of candidates, because it only allows for yea/nay/present. You can, however, use it for a vote on a resolution naming a single candidate to the Speakership.

13) The main difference in conducting the election, of course, is that (1) the House rules in place; (2) the Members of Congress sworn-in as Members rather than Members-elect; and (3) the presiding officer being Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker pro tempore McHenry rather than the Clerk (who presides in the absence of rules and Members). What does this mean in practice? Not a whole lot. One obvious practical difference is that McHenry will likely have the authority in a contested election to recess the House at the call of the chair between ballots,6 rather than having to entertain a motion from the floor to adjourn, and potentially win that vote.

14) The election of the Speaker is of highest constitutional privilege, and takes precedence over other business (Manual §27, see January 7, 1997 attempt to delay Speaker vote until ethics charges settled). Historically, the House has not adopted rules or taken up any business until a Speaker is elected at the outset of a Congress. In an intrasession election, however, it seems reasonable for the House to take up other business. In fact, they did just that in 1814, taking up a resolution thanking former Speaker Clay prior to making a motion to proceed to the election of a new Speaker.

In my view, if they wanted to agree to a resolution regarding the Israel/Hamas war prior to taking up the election, they would be well within their authority to do so. A motion to proceed to the election would be privileged and would need to be defeated if someone made it, but once defeated they could, in my view, take up whatever they want on the floor and return to the election afterwards.

15) As with the January election, under current practice, election of a Speaker in a viva voce election requires a “majority of Members[-elect], voting by surname, a quorum being present.” Under current practice, you do not need an outright majority of the House (i.e. 218) nor do Members who do not vote (or who vote “present”) count. If you get 216, someone else gets 212, and other candidates get a total of 7, you do not win (216/435). But if you get 216, someone else gest 212, and 7 people do not vote (or vote “present”), you do win (216/428).

There are currently 433 Members of the House, 221 Republicans and 212 Democrats. Assuming no Democratic support, a GOP candidate will need 217 votes (217/433) if everyone votes, meaning you can afford 4 GOP defections. If some GOP Members vote present (as happened in January on the final ballot), you can win with fewer positive votes. The general formula for figuring out a win (from the GOP perspective) is: 213 hard yes votes (so that you get more than Jeffries) + any combination of yes/present votes from the remaining 8 GOP Members that add up to 4, with yes votes counting as full votes and present votes counting as half votes.

16) In general, the Speaker pro tempore will immediately move for a subsequent ballot if no Speaker is elected on the first ballot; however, members-elect may seek recognition and upon obtaining the floor may operate under the House rules. This includes making motions, proposing resolutions, moving to table motions, calling for the yeas and nays, and adjourning.

17) If things lock up, the House has procedural options they can try. In the drawn out battles in 1849, 1855-56, and 1859-60, several procedural maneuvers were attempted to break the deadlock. First, numerous attempts to alter the rules were made: to used something like rank-choice voting or runoff voting, where a first ballot would be open, but then candidate getting few votes would not be allowed on the second ballot; or by taking the top few candidates and selecting randomly out of a hat. None of these proposals were ever accepted. They were either defeated or tabled.

One procedure that *was* accepted was plurality voting. In both 1849 and 1855-56, the election was ultimately resolved by the adoption of a resolution that created a plurality winner. The resolution provided for three more regular election votes, and if no one was a majority winner, a fourth vote would be taken and the candidate with the most votes would win. This is how both Cobb and Banks secured election. In each case, the House then passed a resolution declaring them Speaker, which was adopted by a full majority, though then (and now) those resolutions seem superfluous. (See Hinds §§ 221-222)

Finally, in all of the deadlocks in the antebellulm era, a number of members were put up for the Speakership by resolution, getting an up/down vote instead of the open viva voce vote where anyone can vote for any candidate. None of these resolutions were ever adopted, either because they were defeated or tabled.

18) In past multi-ballot Speakership elections, the House has typically taken several votes a day, and then adjourned until the next day. During the January contested election this year, they took 3 ballots on Tuesday, 3 on Wednesday, 5 on Thursday, and 4 on Friday. (Here’s my detailed procedural review of January that I published earlier this year). I suspect in a contested election situation this week, a similar dynamic will emerge; Members get tired of being on the floor, and when there’s no movement in the vote count, adjourning and politicking off the floor makes more sense.

The Politics of This Week

19) I have no strong sense of what is going to happen. I’m not sure anyone does. I can imagine Scalise being Speaker come Thursday morning, after a first ballot win. I can—and I can’t believe I’m saying this—imagine Jordan being Speaker. I can imagine someone we aren’t talking about being Speaker. Heck, I can vaguely imagine McCarthy being Speaker. I can certainly imagine no one being Speaker come this weekend.

20) A lot depends on how much pressure there is inside the GOP for unity and how the potential antagonists weigh the value of party loyalty at this moment vs. fighting to try to extract more benefits in negotiations. As I’ve said repeatedly, a lot of this is normal behavior for a party; party factions fight all the time over leaders and policy decisions. In some ways it’s literally the “stuff” of politics, much more so than elections or roll call votes. It happens to be that most of the time, parties figure these fights out in November/December before Congress starts and you don’t get to see it on the floor. The small margin of power, combined with some Members will to push things to the limit, forced the GOP fight into the open. But don’t kid yourself. Pelosi and the Dems fought this same battle in 2018-2019.

On the other hand, this stuff can be exhausting for a party, and sometimes everyone just throws in the towel to move on. It wouldn’t really surprise me if they came out of the GOP conference looking more united than they have during the 118th, having gone with a candidate that not everyone voted for in the conference but everyone agrees they should vote for on the floor, not having changed the threshold for nomination but just not needing to.

21) My guess is that some of the air has come out of the Freedom Caucus balloon. You can’t just keep making people miserable forever, pressing your every advantage in a group decision-making setting. Eventually, your coalition crumbles and you are just alone. What that tells me is that (1) Gaetz himself will probably be quicker to settle than people might expect; and (2) if he’s not, the people around him will be ready to move on faster than in January. This doesn’t mean the rebels can’t put up a fight. But I think the character and intensity of it will be less than it was in January, or than it was on the floor last Tuesday.

20) Conversely, a lot depends on how driven the moderates are. If they aren’t willing to back up their positions with the credible threat to stop a candidate and/or deal they oppose on the floor, then it really is an asymmetric situation. The GOP moderates are talking quite a bit about changes they want and candidates they do or don’t find acceptable, but unless they are willing to back it up on the floor—or at least threaten to—it’s not obvious to me how much leverage they actually have, in the face of people who have already proven they will.

22) People keep asking me if I think the war in Israel is going to speed up the election. I really don’t know. And I’m not sure we can know. I doubt the race to get a “Sense of the House” resolution on the floor is going to magically make this a one-ballot neat and tidy election. On the other hand, if there’s still a deadlock next week and the administration is looking for something from Congress related to the war, I’m sure that would have a marginal effect.

23) Take this for what it’s worth and what you are paying for it, but if I had to guess, I’d make a bet on an undervalued scenario: Scalise plus reform of Rule IX (so-called motion to vacate), with a side deal to the conservatives about the appropriations bills, and a relatively quick floor fight, maybe just one or two ballots. But again, I have no idea, and I certainly don’t think that’s some sort of favorite to happen.

For completeness, here’s what did happen. On Tuesday, immediately after the resolution agreed to, Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker pro tempore McHenry took the chair, the reading Clerk read a letter from the Acting Clerk that confirmed McHenry was Speaker pro tempore, McHenry read Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) to the House, suggested a rough timeline for the election, and recessed the House at the call of the chair under Rule I, Clause 12(a).

On Wednesday morning, the recess as ended at 10:03am and the House was called to order by Speaker pro tempore McHenry. He immediately declared the House in recess at the call of the Chair. At 3:23pm, the recess was ended and the House was called to order by Speaker pro tempore McHenry. He recognized Mr. Hill, who asked unanimous consent that when the House adjourn, it adjourn to 10am on Friday, and the he moved to adjourn.

On Friday, the House was called to order at 10am. After the prayer, approval of the journal, and pledge, Speaker pro tempore McHenry adjourned the House by unanimous consent until Tuesday, October 10 at 11am.

I actually think it’s totally fine to have the weak version of the SPT for the situation we currently find ourselves in. It might be worth it for the House to differentiate the role of the SPT in a vacancy-but-not-emergency situation from the true continuity of government disaster scenarios.

Some of us are keeping a running tally of Speaker-level authorities McHenry has used over on Twitter: https://x.com/MattGlassman312/status/1709359150541513083?s=20. Please feel free to add to it if you discover any we have missed.

I’m less certain this would make sense for normal Speakership elections at the beginning of a Congress. Since the parties hold their nominations in November, there’s a full 6 weeks for the party candidate to work to secure the support of a House majority.

Speaker Rainey also died in office in 1934, but it was after the sine die adjournment of the 73rd Congress, and no replacement was chosen until the opening of the 74th Congress in January 1935.

It’s not 100% clear if McHenry will have this authority, because the Speaker only has this authority under Rule I, Clause 12(a) when no question is pending before the House. My view is that there is no question pending between ballots in a contested election.

I may be completely wrong here, but I have a question. Given the lack of precedent since the Speaker Pro Tempore rule was updated in 2001, doesn’t the SPT have whatever powers the majority says he has. An example: McHenry calls up a resolution on Israel this week. A Democrat makes a parliamentary point of order that he cannot do that. Who rules on the point of order? McHenry right? So let’s say he denies the point of order. The Democrat then objects to the ruling of the Chair, which is a simple majority vote. Let’s say a majority votes against the appeal. Haven’t we now just added a new power to the SPT? In other words, as long as a majority sustains the ruling of the Chair, doesn’t the Speaker have whatever powers an elected Speaker has? I might be missing something obvious here.