Legislative procedure isn't really hard

It's just like your family deciding where to go to dinner.

I’m going to write a lot in the coming weeks about procedural things going on in Congress. So I thought I’d take a step back and today write about, well, Legislative Procedure, The Mysterious Black Box.™

A lot of peoples’ eyes glaze over almost immediately when they try to figure out what is going on in Congress. And with good reason. If you turn on C-SPAN or look through the legislative action on House Live, it’s a dizzying array of jargon that is beyond Byzantine. Some of the most common things you’ll read or hear sound positively ridiculous:

At the conclusion of debate, the Yeas and Nays were demanded and ordered. Pursuant to the provisions of clause 8, rule XX, the Chair announced that further proceedings on the motion would be postponed. Hmm…

The motion to suspend the rules and pass the bill was agree to by voice vote and the motion to reconsider was laid upon the table without objection. Ok…

The question is on ordering the previous question. WTF?!?!

And these examples don’t even cover the visually disorienting stuff. Like when a vote is called, they post a countdown clock, it gets to zero, 150 Members haven’t voted, and they totally ignore it and keep voting for another twenty minutes.

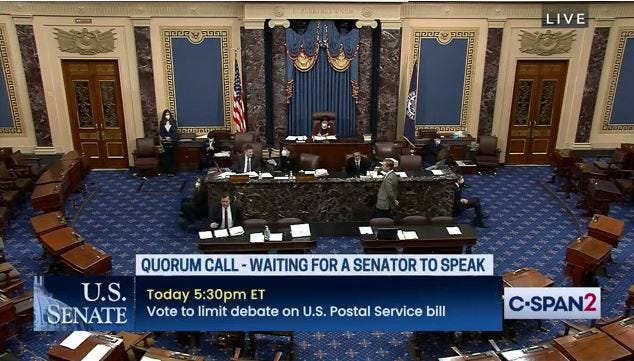

Or—God help you—you turn on C-SPAN2 to watch the Senate, and it always seems to be doing nothing, with the words “QUORUM CALL - WAITING FOR A SENATOR TO SPEAK” at the bottom of the screen and people milling around aimlessly on the floor, time seemingly ceasing to exist.

This is all very confusing. But it’s mostly a mirage. All of the jargon and technical detail and the question is on the previous question stuff is a distraction. If you step back and understand the big-picture of legislative procedure, not only does the insane stuff seem a lot less insane, but it also seems a lot less important to understand.

As my friend Molly Reynolds is fond of saying, the rules aren’t magic. They follow an internal logic that, once you penetrate conceptually, is usually very consistent. And that once you understand conceptually, becomes much easier to follow.

It’s either this or fistfights

Let’s start from scratch. Why does Congress even have all these procedures? Or to put it another way, let’s do a thought experiment. What would the House chamber look like if we didn’t have any procedures?

It would be complete fucking chaos.

There are 435 Members of the House. In the 116th Congress (2019-2020), they collectively proposed 9,067 bills. There’s simply no way the House can consider all of those bills. So who’s bill should go first? I’m pretty sure each Representative—who represents different constituents and interests, and who has lots and lots of personal ideas about how public policy should be altered—has a really good answer that question. Their bill.

And there’s a lot at stake here. Billions of dollars in federal funding is at stake, as is the authority to regulate economic activity of 300+ million people. For many constituents, their very livelihood hangs in the balance of congressional action. And for some, their very lives hang in the balance. To say nothing of how much each Members’ reelection hangs in the balance.

So absent any rules of procedure except what’s in the Constitution,1 the first thing we’d almost certainly have is 435 people standing on the House floor, all screaming to have their bill considered first. This is a recipe for, at best, getting nothing done. And for quite likely starting fistfights.

You do this constantly with your family

But here’s the thing: this isn’t unique to Congress. It’s true of any collective decision. Group decision-making requires procedures. Take any mundane example. A family of five deciding what to eat for dinner. A couple choosing what to do on Saturday night. Kids deciding what game to play in the yard. All of these are group decisions, and all of them follow procedures. Those procedures probably aren’t written down, and they may be vague. But the decision rules exist.

In fact, you can boil the rules for group decision-making down to how you answer three questions:

What proposal are we going to consider.

How long are we going to consider it.

How are we going to make changes to the proposal.

That’s it. These are the core elements of legislative procedure, and also the core elements of all group decision-making. What proposal are we going to talk consider—that’s the agenda. How long are we going to consider it—that’s the debate. And how are we going to make changes to the proposal, that’s the deliberations.2

The rules surrounding these three things—the agenda, the debate, and the deliberations—are all you really need to know about any system of group decision-making.

And control of these things is where power comes from. When we say someone has a lot of procedural power, that’s we mean.3 They have influence over the agenda, the terms of debate, and the terms of deliberation.4

Let’s go back to one of my examples. Imagine I gather my wife and three daughters and say “we were going to eat leftovers here for dinner tonight, but I think we should go out to dinner. How about Taco Bamba?”

I’ve just initiated a group decision-making situation, and I’ve also already answered some of the key procedural questions. I set the agenda (we are going to consider going out to dinner, at Taco Bamba). I’ve implicitly set the terms of debate (we’re going to have some debate for an unspecified amount of time), and I’ve also set some vague terms of deliberation (I’m going to allow some).5

Under these implicit rules, my wife might argue against the proposal. I don’t want to go out to dinner. Let’s just eat here. My youngest daughter might offer a substitute amendment—I think we should go see a movie, and just grab snacks at the theater. Or another kid might offer a perfecting amendment—I think we should go Taco Bamba, but not until 8pm.

We can debate all of these. Or not—if everyone else hates my youngest daughters movie idea, we will probably immediately table the amendment and move on. But maybe people aren’t so sure about the 8pm perfecting amendment. So maybe we go around and discuss timing. There might even be another amendment, for 7pm. We can discuss that. And then we can vote,6 on both whether to go out to dinner and at what time.7 And then we will come to a decision.

Congress is just a formalized fight over eating out

This is essentially the same process that goes on in the House and Senate. The Members set an agenda, they decide how long we are going to debate something, and they decide how we are going to make changes to the proposal.

Of course, we need to answer those questions—if we don’t have rules about how to set the agenda, the debate, and the deliberation, we’re right back to the chaos on the floor and the fistfights. The House and Senate are not setup like an informal family meeting, where the terms of procedure are unspoken, and often just collegial in nature. Remember, there are billions of dollars and lives at stake here for the members.

So how do we answer the questions about the rules of procedure? How does Congress set the agenda, the terms of debate, and the terms of deliberation?

The answer is that we have written rules. Lots of them. The Constitution provides some basic structure, most notably in its authorization of the House and Senate to determine their own rules of proceeding.8 Both chambers, thus, have their own standing rules.9

Of course, these rules can’t cover every possible situation in perfect detail, so both the House and Senate have to regularly interpret their rules for novel situations.10 These precedents are compiled and tracked and used to guide future situations.11 House and Senate rules also sometimes make it into statutory law.12 A large set of unenforceable norms also structure chamber procedures, as do the (unenforceable) rules of things like party organizations that exist on the Hill.13

One question you might have is this: how are all these rules enforced? That’s an important question. The most important thing to know is that the rules of the House and Senate are not self-enforcing. There is no neutral referee who blows the whistle if someone does something contrary to the written rules. If the Members collectively do not want to follow their rules—if not one objects to just doing it differently—then it’s totally fine to just do it differently. There’s a difference between how the rule are written and how they work in practice.14

That said, if the rules are being violated, any individual member can demand they be followed by making a point of order. Essentially you just stand up and say “the rules do not allow what is currently happening.”15 At that point, the person in the chair will make a ruling—guided by the parliamentarian’s advice as to existing precedent on the issue—as to whether you are correct in your point of order. Whichever side loses the ruling has the opportunity to appeal, and that appeal goes to a vote of the chamber. If the chamber overturns the ruling of the chair, you typically have a new precedent.

Seriously, it’s no different than an HOA meeting

Ok, so let’s talk now generally about how parliamentary procedure works at a nuts and bolts level. The cool thing is that most groups that have formal rules of decision making actually look a lot like the House and Senate. If you’ve ever used Robert’s Rules of Order at an HOA or local club meeting, you are already pretty familiar with congressional procedure.16

The basic building blocks are as follows:

There is one person who is in charge of managing the proceedings. Call them the presiding officer. They might have a lot of procedural power (like the Speaker of the House) or very little procedural power (like the President of the Senate). But at a bare minimum, they are going to call on people.

Only one person can talk at a time. This person is said to have the floor or be holding the floor. If you don’t have the floor, you can’t talk. So one important question, of course, is how you get the floor. As it turns out, getting the floor is totally different in the House and Senate, and these different processes for getting it lead to very different dynamics in the two chambers.

Once you have the floor, you can operate under the rules. You can try to set the agenda, to the degree the rules allow. You can debate—that is, you can talk about the current proposals—to the extent the rules allow. You can also deliberate—that is, you can try to alter the current proposal, again to the degree the rules allow. Most importantly, if you do not have the floor, you cannot do any of these things.17

If you have the floor and want to debate (or if the rules by which you got the floor only allow you to debate), you may or may not be constrained. In a lot of HOA meetings or town councils, you might have a three minute time limit. In the United States Senate, you typically have unlimited time.

If you have the floor and, to the extend allowed by the rules, want to set the agenda or deliberate, you will typically do this by making a motion. Motions are the basic building block of legislative procedure. I move that we take up the proposal for a new diving board is an agenda setting motion. I move that we amend the dinner proposal by adding “at 8pm” to the end of the proposal is a deliberating motion. In many parliamentary situations, you lose the floor upon making an motion.

Every motion ultimately needs to be disposed of, one way or another. Either by a direct vote on the motion, or a vote to table the motion or it being withdrawn by the person who made it, or by the operation of another rule rendering it disposed of by rule.

Let’s use an HOA meeting as an example. Under the rules of the HOA, the elected President of the HOA is the presiding officer at the monthly meeting. She calls the meeting to order. The rules of the HOA say the president gets the floor first and may make a proposal. She makes a motion to approve $250 in spending to upgrade landscaping at entrance to neighborhood. That sets the agenda.

Two people raise their hand, and the president recognizes the first one, who now has they floor. He argues against the proposal as too much money, says we should only spend $100, and makes a motion to amend the proposal to $100, and thus loses the floor. The next person gets the floor and argues in favor of $250. When they finish debating, they yield the floor without making a motion.

A fourth person gets the floor and speaks vociferously in favor of $150. He will not yield the floor, so a fifth person makes a point of order that, under the HOA rules, no one can speak for more than five minutes on a question. The presiding officer agrees and the bloviator loses the floor. A sixth person get the floor talks about needing more info, and moves to delay the proposal until next week. A vote is immediately taken, but fails.

No one else seeks the floor. Debate is closed. The first vote is on the amendment to reduce the amount to $100. The vote passes. The next vote is on the actual proposal, which now proposes spending $100 to upgrade the entrance landscaping. It passes.

The floor is now open for new agenda items.

That’s 95% of all legislative procedure

That’s how the House and Senate work. Not in the details—all legislative bodies use somewhat distinctive procedures, House and Senate no exception—but they really are no different in concept.

The rules provide for agenda setting, debate, and deliberation. Members preside, get control of the floor, set agendas, debate, and deliberate to the extent allowed by the rules. Motions are made and disposed of. Things pass, or they don’t. And then new proposals are made.

The distinctiveness is only in the details, and once you understand the concepts, the details sort of fall into place, because you know the right questions to ask. How do you get a bill on the House floor? When can you offer an amendments in the Senate? How long can you hold the floor in the House for debate? And, most importantly, how do you stop someone from doing all these things if you don’t like their proposals. One answer—always—is to defeat them in a vote. But the procedural power is finding ways to defeat them, even when you don’t have the votes.

The answers to these questions, of course, are different in the House and Senate. And this blog post is not about the details. But it probably is important to think about the House and Senate as conceptually different in how they address the general principles of legislative procedure.

House procedures tend to reflect:

Majority rule

Limits on debate

Constraints on deliberation

A strong presiding officer with some discretionary recognition power

The Senate procedures tend to emphasize:

individual rights of Senators over majority rule

Freedom to debate without limitation

Freedom to deliberate

A weak presiding officer with little discretionary recognition power

These rules reflect the different structure, culture, and composition of the two chambers, and also a fair amount of historical happenstance. The sum total of these rules is that the House operates in a manner that ultimately results, relative to the Senate, in prioritizing decided majoritarian outcomes over deliberation, while the Senate tends to emphasize extended debate and deliberation, even at the expense of outcomes and majority rule.

The Constitution does not provide a lot of guidance for congressional procedure. It requires each chamber to keep a journal (this is not the congressional record—that’s a substantially verbatim record of the entire debate; the required journal is more like the minutes of a meeting); it requires that a quorum (majority of the members) be present to do business; and it requires that a recorded vote be taken if 1/5 of the members present demand one.

Virtually everything else about legislative procedure is explicitly left up to the House and Senate themselves, in Article I, section 5, clause 2: Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.

This distinction between debating and deliberating is important, IMO. A lot of people use them interchangeably, but a strict definition under which debate mean “arguing for or against proposals” and deliberation means “suggesting and voting on modification to proposals” is helpful in keeping things straight. You can have debate without deliberation (this is very common in group decision-making, including in Congress) and you can have deliberation without debate (less common, but occasional in Congress—happens in a Vote-A-Rama in the Senate—but surprisingly useful in group decision-making.)

Of course, there other types of power in group decision-making, like substantive influence. That’s, for example, the ability to get people to change their vote on a bill and join your side. It’s obviously very important, but it’s not procedural power. Maybe you are good at debate and can convince people to change their mind and vote against me. But if I can set the terms of debate—and I set them to “no debate”—your substantive influence may be negated by my procedural power.

The most famous quote on this is from Representative Dingell, who once said “If you let me write the procedure and I let you write the substance, I'll beat you every time.”

Lots of alternative structures of procedure could be used here. I could have even said, “we’re not having leftovers. We’re going to Taco Bamba for dinner. Get in the car.” In that case, I would have set the agenda, allowed no debate, and allowed no deliberation. Heck, I didn’t even allow a vote. The proposal was simply adopted.

Obviously, the voting rules are just as important as any other procedure in regard to outcomes. Are everyone’s vote equal, or do Mom and Dad’s count for more? Do we need a bare majority, supermajority, or unanimous vote? What order do we vote on various proposals?

Things can get really tricky here. Usually, in a family spot like this the decision to go out will be voted on (at least implicitly) before the timing amendment gets taken up. But maybe my wife is willing to relent on the leftovers, but only if we go out at a particular time. Maybe she put in the 7pm amendment. If two of the kids won’t budge off 8pm because there’s a TV show they want to see at 7pm, we might have a majority to stick with the leftovers, even though there’s a majority that prefers out to eat over leftovers. I didn’t say it wasn’t going to make you pull your hair out substantively.

See footnote 1.

The House adopts standing rules at the beginning of each Congress, by majority vote. (Here are the 117th rules. Typically they are very similar to the previous Congress, but there are always a few changes here and there). The Senate considers itself a continuing body—remember, 2/3 of the members are not up for election in any given federal election—and thus does not regularly revisit its rules on any schedule. The standing rules of both chambers provide for means to alter the rules at any point in time.

Example: the House requires that all amendments be germane (i.e. related) to the measure being amended. But that’s an endlessly complicated question. Is an amendment about gun rights in DC germane to a bill about DC voting rights? Is an amendment about space-based military weapons germane to a NASA spaceflight bill? So the House has built up a massive number of precedents related to questions of what is and isn’t germane.

The House precedents run a serious number of linear feet in the shelf, but the easiest quick guides to House precedents are the annotated rules and a book the Parliamentarian’s office puts together called House Practice. The Senate has a similar volume (Riddick’s) but it’s long out-of-date and the Senate does not compile precedents regularly in a public location.

Examples of this include the Budget Act and BRAC, both of which provide statutory rulemaking provisions for the House and Senate that allow for expedited consideration (agenda setting!) of certain types of legislation in certain situations. Rules made in this manner can be overridden by either the House or Senate choosing to adopt new rules on their own, without the need for a new law; otherwise, the president would have some level of control over chamber rules.

An example of this is the past rule of the House Republican Conference that prohibited GOP leaders from bringing bills to the floor that included earmarks. While this rule was not enforceable on the floor—no one could make a point of order that it was being violated, since it wasn’t a House rule, your only recourse if it was violated was to take it up with the party—it nevertheless structured an enormous amount of decision-making in the chamber.

If any of you sit on an HOA board or the governing board of a church or a pool club, you’ll be familiar with this. The rules might specify very strict procedures, but things may be done by consensus. The rules may make all sorts of detailed provisions, but the vast majority of meetings may operate seemingly outside of those rules, not breaking them but not employing them.

Rules can also be used strategically. Their intended use my stray far from their actual use. This is most obviously true of the filibuster in the Senate. But it’s also true for a wide number of rules in both chambers. In fact, the rules of the House for changing the rules themselves are used strategically almost every day in the House to shape the agenda, the debate, and the deliberation, away from where it would naturally go under the rules.

Politics can come into play here. In March 2020, leaders of both parties had agreed to pass a COVID relief bill by unanimous consent—a procedure that would allow the vast majority of Members to stay in their districts and not risk coming to DC with the virus raging. If every Member wants to ignore the rules, that’s fine.

Representative Massie (KY-4), however, did not think this was proper—with $2.2T in spending on the line, he wanted everyone on record how they voted—and he threatened to stay in DC and raise a point of order that no quorum was present if the leaders tried their gambit. The result was that a quorum of Members had to return to Washington to take the vote. The upshot was that the rules were followed, but also that many Members became extremely angry at Massie. And so Members need to consider wider politics when seeking to enforce the rules.

Both the House and Senate rules are rooted in Jefferson’s Manual, the parliamentary guide Thomas Jefferson put together in the early 19th century, and which predates Robert’s Rules of Order by about 75 years. But legislative procedure is legislative procedure, and in the big picture the two works are much more similar than they are different.

In most cases, you cannot break into someone else’s control of the floor. You have to wait your turn. One prominent exception is if you are making a point of order, which often has the ability to interrupt another person’s control of the floor.

Saved for my next offering of my Intro American and Legislative Process classes. Thanks, Matt!

This is really excellent, and you now have me thinking about reframing the way I introduce legislative process in my intro and Congress classes.