The '24 Election and Institutional Change

Elections create different short-term politics, but that can matter long-term

The 118th Congress—to be fair, mostly the House of Representatives—has been one heck of a wild ride. In January 2023, it took 15 ballots to elect Speaker McCarthy, the first multi-ballot Speaker election since 1923. McCarthy lasted less than 10 months, becoming the first Speaker ever removed by the House. His deal with the GOP Freedom Caucus to secure the Speakership—including putting people on the Rules Committee who were not loyal to the Speaker—collapsed when he put a bipartisan CR on the floor via the suspension process to avoid a shutdown. This came on the heels of a rocky period where the GOP leadership was defeated repeatedly in trying to bring bills to the floor via special rules, after McCarthy angered his right-wing by using Democratic votes to pass the debt limit deal.

It took more than 3 weeks and four nominations to elect Mike Johnson as McCarthy’s successor, as GOP party loyalty completely ruptured. During that period, Rep. McHenry presided as the first Rule 1, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker Pro Tempore, but—with everyone unclear about his powers—the House ceased to function as a legislature. Johnson has fared somewhat better than McCarthy—the movement to oust him from the Speakership failed, as Democrats helped sustain him. This came on the heels of a bipartisan vote in the Rules Committee to move a set of foreign aid bills, which had the dual problem of not enough GOP votes for a special rule, and not enough Dem support to move via suspension, meaning their original omnibus packaging had to be broken up, Compromise of 1850-style. This ended talk of even more unusual strategies for the bills, including the rarely-used discharge petition (which was later used successfully!) and the almost-unheard-of defeat of the Previous Question.

The exotic developments were not limited to party struggles over policy. The House expelled a Member. There have been occasional duels over censuring people on the House floor, a number of them successful. A cabinet Secretary was impeached for only the second time ever, but only on the second try, as the first vote failed. Committee hearings have turned into complete circuses of personality. Members’ words are being taken down. And droves of powerful Members announced they were retiring from Congress, including the Chair of the Appropriations Committee handing back the gavel mid-session.

A lot of people will attribute this to the dysfunction of the House Republicans. And that’s definitely a big—and crucial—part of the story. But there are two other crucial pieces of the story. First, the narrow majorities in the House. Much of what we have seen in the 118th would not be happening if the GOP had won the larger House majority many people were expecting in the 2022 election. Had the GOP won 235 or 240 seats in the House—as some forecasts were predicting—the Freedom Caucus would not have held the balance of power, McCarthy would not have had to bargain with them, and the House probably would have functioned much more normally.1

Second—and what I’d like to focus on in the rest of this piece—is the institutional structure of the government, at the highest level. The arrangement of partisan control in Washington—with a Democrat in the White House, Democrats controlling the Senate, and the opposition Republicans controlling the House—is a key driver of the shape of politics during any Congress. And that was absolutely true in the 118th Congress. Armed with little positive legislative power—there’s basically nothing the House can do unilaterally on the law-making side of things—the House GOP was necessarily going to be focused on messaging and administration oversight, with the leadership stuck having to bargain with Dems over must-pass legislation that the right wing hates. This was the easiest prediction in the world, and everyone in Washington made it.

Enter the 2024 election and the 119th Congress.

Presumably, if you are reading this newsletter, you are aware that the 2024 federal elections will include the selection of (1) the president of the United States for the term of January 20, 2025 to January 20, 2029, (2) Representatives for all 435 seats in the House of for the term of January 3, 2025 to January 3, 2027, and (3) Senators for 34 seats, 33 for the term of January 3, 2025 to January 3, 20312 and one special election in Nebraska for the remainder of former Senator Sasse’s term, which ends on January 3, 2027.

The results of these elections will obviously shape political outcomes in the United States across a host of policy areas. Will the Trump tax cuts be extended? How much will the government spend on SNAP? What will be our foreign policy toward Russia and China and Canada? Elections matter, and 2024 is no exception. Policy outcomes will be different, based on which candidates and parties the voters elect. Simple as that. Democracy.

But the elections will also shape the context for institutional developments in the government: within Congress, within the presidency, and between the branches of government. And this will potentially have longer-lasting effects than the individual policy choices made by the 119th Congress.

Institutional Change Is Largely Driven by Short-term Politics, Not Normative Ideas

When I was working at the Congressional Research Service, part of my portfolio was institutional issues in Congress, including separation of powers. This led me to spend a lot of time banging my head against the wall with Members and staff as I tried to help them figure out how to reign in the president and executive branch on any number of issues: war powers, vacancy appointments, responses to congressional subpoenas, rulemaking, and more things than I can count in appropriations world.

I was working in a non-partisan and ideological-neutral capacity—my mission was simply to help the Members and staffers achieve their goals—and the first thing you notice when that’s your approach is that political actors often have genuine normative views on institutional questions, but those views are almost completely dominated by short-term substantive goals. That is, the rules are almost completely instrumental to the underlying substantive outcomes. People just want policies. And they don’t really care how they get them or what has to change in order to get them.

I’m not telling you anything you don’t already know. Everyone and their brother can explain to you how support for the filibuster works: if you are in the majority in the Senate, you complain about it as the death of democracy; if you are in the minority in the Senate, you defend it as the very essence of the republic. And then when you switch roles, you switch positions. No sweat. Ditto with presidential power. Other party got the White House? Congrats, you just became a Whig. Now your party has it? Well, let’s get the executive orders rolling, there’s stuff to do!

And while that hypocrisy is the stuff of democratic politics, the piling up of these short-term instrumental calculations about institutions leads to long-term developments. The most famous of which, of course, is the slow draining of power away from the legislature toward the presidency. Partisan majorities continually augment presidential power in order to achieve substantive goals; the opposition kicks and screams, but never really seeks to reign-in the presidency. Instead, they angle to get control of the White House, and once they do they seek to use the tools of the presidency for substantive goals of their own. Rinse and repeat.

And so elections themselves alter institutional development, because they arrange the balance of power in the institutions, which in turn sets up the politics for the following Congress, including how the substantive issues interact with the institutions. Here’s a vivid example: I spent some time at CRS in 2016 working on something called the Article One Initiative, which was a Federalist Society project about restoring legislative branch power, but also very popular at the time among House Republicans, because in the short-term it was essentially a push to curtail the Obama administration. Fine, that’s politics.

But it also appealed to a lot of Congress-types (like me) as a normative good, to help build congressional capacity and restore a balance of power between the branches that many people around town—liberal and conservative—were worried about in the wake of 9/11 expansions of presidential power. And so in my capacity at CRS I was doing a lot of work with House GOP leadership staff on various pieces of the puzzle and approaches to making positive changes to empower the legislature. Some of it had the feel of what became the House Committee on Modernization, but a lot of it was bigger scope, things like sunsetting AUMFs or even restoring the legislative veto.

And in the summer of 2016, a lot of people on the Hill thought the 2016 election was going to open the perfect window for the politics to match up with the normative goals. Most people were more or less convinced that Clinton was going to win the presidency, and a heck of a lot of people though the GOP was going to hold onto the House and Senate. That arrangement of the balance of power—a lightning rod of a partisan president, combined with an opposition Congress—might just do the trick. If good-government Dems (perhaps with memories of fighting Bush 43) could be brought on board, maybe there could actually be a supermajority for some serious Article One moves.

And then the 2016 election happened. Unified government for the Republicans. I’m not kidding when I say it caught them completely flat-footed on the Hill. They were not going to be an opposition party. I remember calling over to one of the leadership staffers a few weeks after the election, just to see what the status was of the Article One stuff. “Uh, yeah, we’re going to be going a different direction.”

And that was that.

And look, this isn’t just about battles with the president. You can find examples of this stuff everywhere. Remember last October when we were all debating how much power Speaker Pro Tempore McHenry had? Democrats pretty quickly came around to the idea that he had very limited power. Maybe they genuinely believed that—some of them surely did—but one big reason they took that point of view is that McHenry unceremoniously used the Rule I, clause 3 authority of the Speaker to kick former-Speaker Pelosi out of her Capitol office space.

It was a petty move—and I still don’t really understand why he did it—but I know the effect it had: all of a sudden the Dems had a substantive reason to be outraged about McHenry’s power, and in turn it made them strong backers of the idea that a Rule I, Clause 8(b)(3) Speaker Pro Tempore has no power beyond holding the election for the new Speaker.

In my view, this is a normative mistake. A future temporary Speaker coming in after a vacancy might arrive like McHenry did, amid an intra-party squabble; but they might also arrive in a dire national emergency, and I’d be a lot more comfortable with the vacancy provisions knowing the temporary Speaker had the authority to put a suspension bill on the floor without having to conduct an election first. And look, there really was left to substantive chance. If McHenry’s first move as Speaker Pro Tempore was to recognize a Member to put the foreign aid bill on the floor as a suspension, I think the Dems go for it. And the entire institutional understanding of the temporary Speaker Pro Tempore exists under a different set of precedents, and with a completely different amount of power.

What will the structure of power be next year?

You can think of the partisan balance of power in the elected branches of government as three separate flips of a coin. Heads the GOP gets control, tails the Dems get it. Consequently, there are eight partisan configurations of the presidency, the House, and the Senate. They can be written out in shorthand like this: DDD, DDR, DRD, DRR, RDD, RDR, RRD, RRR.

Three of these combinations (RDR, RDD, and DDR) are very unlikely, reflecting the reality that if would be quite surprising if the Democrats did well enough to keep control of the Senate but did not manage to take the House or hold the presidency.

Of course, we aren’t actually dealing with coin flips here. The probabilities of each party getting control of the various branches differ and reflects public opinion about the elections in the each district and state. So maybe we’re flipping weighted coins. And so you might build a naive model of these probabilities by simply multiplying out the current individual betting markets for the presidency, House, and Senate to figure out the rough probabilities of each of the eight combinations.

The problem with that strategy is that the elections to the three bodies are not hindependent events like weighted coin flips ; a party that wins the presidency is much more likely to win control of the other two chambers than it is to control those chambers if it loses the presidency.

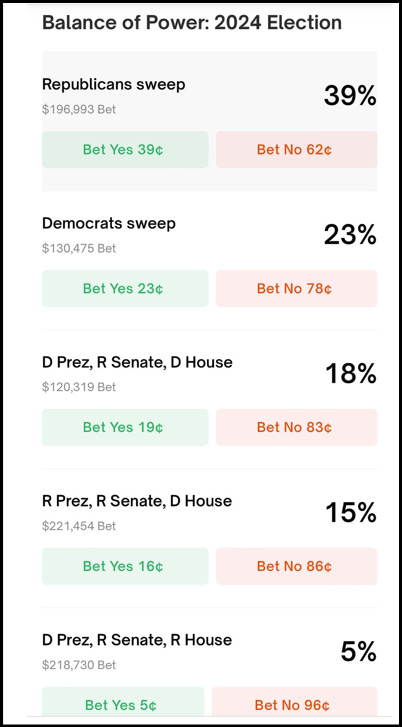

Luckily, Polymarket has an actual betting market on the balance of power, in which bettors can take positions on each of the eight possible combinations. Here are the current numbers you can bet on as of this morning, excluding the three highly unlikely combinations (whose probabilities are all below 1%).

These numbers surprised me—and some other Hill folks—because I would definitely say that the conventional wisdom on the Hill has the RRD and DRR scenarios as much more likely than they are currently priced (15% and 5%). Now, political prediction markets are definitely fallible. And the beauty of them is that if you think they’re wrong, you can financially benefit simply by entering the market. But the fact that I haven’t yet done so is some evidence I’m not as sure about my impression of the Hill conventional wisdom as I thought I was.

What are the institutional consequences of these various arrangements?

That was probably a bit too much throat-clearing to get to what I’m actually interested in thinking about right now: how will these various outcomes in the partisan arrangement of the balance of power potentially affect major questions of institutional development in Congress and the presidency. What follows is not a complete guide to the institutional landscape, but a brief survey of some of larger institutional questions that will be shaped by the results of the 2024 election.

GOP/Dem Sweep (62% current likelihood) : What happens to the legislative filibuster and/or reconciliation in the Senate?

Unified governments—Republican or Democrat—virtually always attempt to do some party-line legislating. The last five presidencies (Clinton, Bush 43, Obama, Trump, and Biden) have all begun with unified governments, and all have attempted at least some party-line legislating.

Many of these attempts have included use of the budget reconciliation process to circumvent the filibuster in the Senate. The Inflation Reduction Act did. The American Rescue Plan did. The Trump Tax cuts did. The 2017 attempt to repeal Obamacare did. Obamacare itself did. Lots of stuff before that which I can remember did.

Through the course of this substantive party-line legislating, the reconciliation process—a method designed, at least in theory, for quickly and more easily getting spending in line with revenues—has undergone institutional changes that make it basically unrecognizable in the context of its original intent. In recent years, parties have put together multiple so-called “shell” budget resolutions. so late in the process as to be meaningless for the budget, and used the related reconciliation instructions to expand the deficit, rather than, you know, reconcile it.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with this; legislative practices always change as actors seek to use existing institutional tools to achieve substantive goals. That’s half the point here. But make no mistake, the budget resolution reconciliation process is nothing more than a pass-through mechanism for majorities to get around the filibuster, perhaps the best example of what Molly Reynolds would call an exception to the rule, a way the Senate can avoid a filibuster without actually killing the filibuster.

So I would expect continued aggressive expansion of the reconciliation process in any unified government. In fact, Republicans are already talking to the parliamentarian about the scope of potential topics that could be included in a reconciliation bill. The tricky part is that reconciliation, under Senate rules and precedents, is limited to budget-related legislation.

The Senate itself is in control of what that means, but most Senators have typically tended to defer to the parliamentarian’s interpretation of what is and isn’t eligible. Could that change? Sure. The Senate could overrule the chair acting on the parliamentarian’s advice. Or the Senate majority could just fire the parliamentarian. It’s happened before.

The comes up largely because two different social issues are driving a big part of the agenda in public politics right now: immigration and abortion. Some aspects of these issues are budget-related, but at their core they just aren’t. Democrats were rebuffed by the parliamentarian about immigration in reconciliation bills several years back, and everyone pretty much agrees that something like a 15-week abortion ban or a statutory protection for a second-trimester abortion would not be eligible for inclusion in a reconciliation bill.

And this is where filibuster reform comes in. If the reconciliation process is unusable, my sense is that a unified government is going to have a very difficult time resisting the opportunity to make immigration and/or abortion policy by moving to (at least partially) end the legislative filibuster. The Dobbs decision has put abortion front and center for both parties, and while DC gridlock may very well retain it as largely a state issue for some amount of time, I suspect majorities in Congress would like to act on this, federalism be damned.

Mechanically, it’s not a challenge; the procedural steps for a bare majority to use the so-called nuclear option are well-understood, and when the filibuster was ended on nominations (for lower courts and executive nominations in 2013; for the Supreme Court in 2017) it took just a handful of minutes on the floor. The question is whether a Senate majority has the will to do it.3 And the unlocking of the abortion issue as a live legislative question dramatically increases the probability they will. Democrats are already talking about.

On the other side of that coin is a whole new world: a majoritarian Senate would have large ramifications for legislation, Senate bargaining, House-Senate relations, agenda-setting on the Hill, and the power of individual Senators. It’s probably not an exaggeration to say it would be the biggest institutional change on the Hill in decades, if not generations. And look, you have to have the votes. A majority of 51 might fail on the backs of some process-hawks. So even if a unified government would like to kill or reform the filibuster, they may not be able to.

But make no mistake, the current filibuster practices in the Senate—in which the minority filibusters literally everything—are not a stable equilibrium. And honestly, they’ve only been around since 2010. I expect them to fall sooner or later. Now, the Senate can stay irrational perhaps longer than you can stay sane. But the rise of the hot-blooded social issues may just be the key ingredient to push a unified government to take the plunge.

BIDEN/R Senate/D House (18%): Will we see a blockade of judicial or executive branch nominations?

If we do not have a unified government, you won’t see filibuster reform. Period. But opposition control of the Senate could unleash another consequential institutional development: a major partisan breakdown of the nominations process.

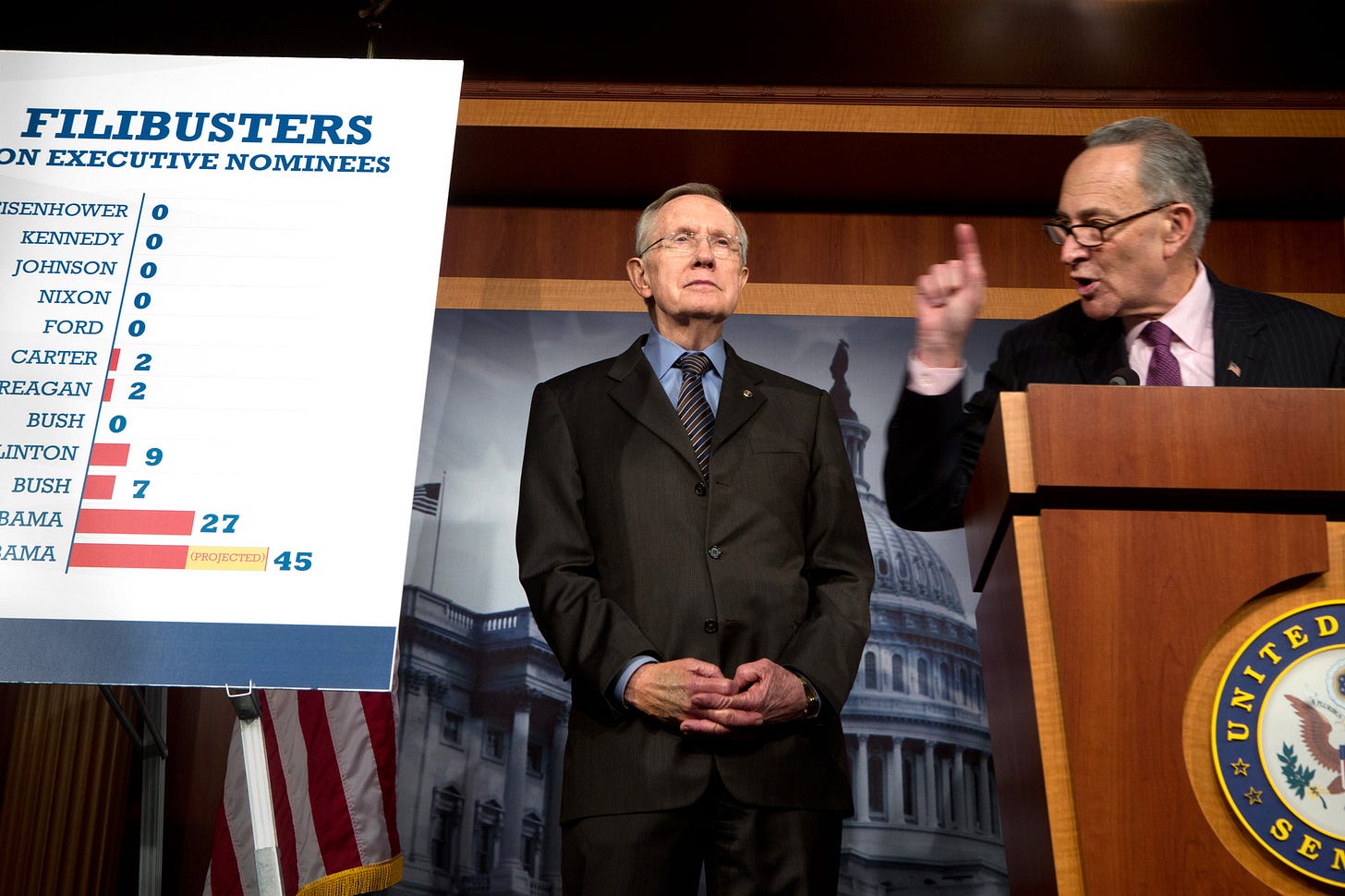

If you recall, the filibuster on nominations was ended in 2013 by Harry Reid and the majority Democrats because (correctly, in my view) they believed the Republican minority had turned the nomination filibuster into something closer to an outright blockade, no longer using it selectively to curtail individual picks, but as a strategy for keeping Democratic appointees off the bench, wholesale.

This had been building for a while, and the Democrats weren’t blameless in the war of the escalating use of nominations filibusters—heck, Republicans will tell you Dems started the whole thing with the filibuster of the Bork nomination, and that’s got some element of truth to it—but McConnell and the GOP definitely took it to new heights during the Obama administration.

Once Reid acted, things settled down. Until 2015. That’s when the GOP took control of the Senate for the 114th Congress. Now it didn’t matter that the filibuster had been ended, because the GOP had the Senate majority and could just vote down any nominees sent over from the White House. Or, more likely, simply not take them up on the floor. Nominations didn’t come to a complete halt in 2015 and 2016, but they did slow down dramatically.

This culminated with the refusal of the Senate to consider the nomination of Merrick Garland to the Supreme Court, after the death of Justice Scalia.4 Majority Leader McConnell basically made a bet that not taking up the nomination would not be punished by the voters in the 2016 election, and holding the seat open would give the GOP some chance to fill it if they could win the presidency. It seemed like a longshot with Trump as the nominee, and it could have backfired—Clinton might have nominated someone other than Garland who was much more liberal. But it didn’t.5

Garland might have been a preview of the Senate to come—blockades of nominations by opposition parties—except that a peculiar thing happened: since 2017 the Senate has been continuously controlled by the party that holds the presidency. The issue of a judicial (or executive nominations) blockade hasn’t come up, because the partisan structure of the government hasn’t aligned for it. Instead, with the filibuster gone, both President Trump and President Biden have enjoyed record-numbers of judicial confirmations. Sometimes it feels like it’s the only thing the Senate does.

But the partisan animosity over the judiciary has not receded. In fact, it’s probably significantly worse now than it was in 2016. And so a reelection of President Biden and the taking of the Senate by the Republicans (or the highly unlikely combination of President Trump and a Dem-controlled Senate) is going to instantly ignite the possibility of judicial nominees slowing to a trickle.

I don’t think you will see anything as severe as a complete judicial blockade; many lower court judges still sail through with big bipartisan votes. And most executive branch nominees still benefit from the belief by many Senators that the president is entitled to have his team in the administration, and are further protected by the vacancy Act, which allows the president to fill them with Acting heads in many circumstances.

But could a Supreme Court seat be left open indefinitely? Sure. And could the judicial workload emergencies that Chief Justice Roberts worries about so much get worse? Sure. And none of that seems great.

TRUMP/ R Senate/ D House (15%): Will the House Dems adopt the tactics and problems of the 118th GOP?

Imagine a mirror image of the 118th Congress, in which it’s the Democrats holding the House by a narrow majority, and the GOP in control of the presidency and the Senate. Any concerns about a judicial blockade fall by the wayside, as we get another two years of unified presidency-Senate control. But all of a sudden, it’s the Dems who are faced with a narrow majority and an institutional structure that leaves them little more than the oversight-and-messaging incentives currently at play in the House.

Does the House become a mirror-image shitshow?

I think it depends on what we man by shitshow. If Trump wins the presidency, you are definitely going to see an absolute freak-out by a Democratic-controlled House. Just judging by the 117th Congress, we know that the investigations, oversight, and rhetoric will ramp up significantly. And that’s not bad—opposition parties always do better oversight of the administration, though you have to take the partisan political stuff aimed at embarrassing the administration along with the good-government stuff on budgets and implementation that opposition parties do by their very nature.

I imagine the yelling will be even louder this time. The investigations will likely have more legal action over subpoenas. You’ll definitely get impeachment resolutions coming to the floor via Questions of Privilege, and it wouldn’t surprise me at all if you eventually got an actual impeachment of an executive branch official, if not Trump himself. You might get hardball on the appropriations process, up to and including a possible government shutdown over particular Trump policies and associated limitation provisions. It will be heated.

But I’m very torn on how much this partisan arrangement will reproduce the internal party problems that the GOP has faced in the 118th Congress. For one, I don’t think the Dems have anything near the House Freedom Caucus on their left. The progressives can get annoyed at the leadership, and the so-called Squad will occasionally try to hijack the agenda in the public sphere, but there’s not a lot of evidence that the Dems have a left-wing faction ready to play the type of legislative hardball necessary to force things on the floor.

And while some very smart observers of the Hill have been saying the left-wing version of the party crackup has been coming, it all still seems very asymmetric to me. The Dem left seems interested in policy bargaining, whereas the Freedom Caucus has basically become addicted to losing to prove a point.

But this may be underestimating how much Members are learning in the 118th. If the Dems have a narrow majority, the first test will be the Speaker election. The McCarthy fight in January 2023 was unusual because it carried over to the floor, but the process itself—Speaker candidate bargains with factions and trades things for their support—is the most normal party politics thing you can imagine. Pelosi had done it just 4 years earlier, as a faction of 16 Dems signed a letter refusing to vote for her for Speaker. So she bargained with them in November and December and bought up the votes. Totally normal.

I don’t doubt Jeffries will be Speaker in this configuration, and I don’t doubt he will win on the first ballot. But I do wonder what he will have to give up to get it. Could the squad or the progressives demand Rules Committee seats for people who aren’t entirely loyal to the leadership? Will they balk at reforming the so-called motion to vacate? Will they organize themselves before the Speaker election and rules adoption as a bargaining unit that has to be dealt with as a block? All these things seem vaguely possible.

And the thing that gives me the most pause is the thing that was missing previously: what’s the burning issue divides the left from the Dem leadership? That would have been a hard question, until the Israel-Hamas war started. Now it’s plainly evident. Would the Dem Left vote for more aid to Israel? They didn’t this time, why would they next time, under Trump. Is the issue hot enough for them that they might threaten the Speaker existentially over it? That’s much harder to tell.

My instincts on this are all “no.” That the GOP House issues are fundamentally different than the divisions among the Dems. I think Jeffries is more in control of his caucus than McCarthy ever was. And I think a Trump presidency would work to unify the Dem left with the Dem leadership. But I’m not ready to bet my House on it.

BIDEN/R Senate / R House (5%): Does presidential power come under a successful attack?

The final scenario features what you might call “traditional” divided government, rather than “divided Congress.” It harkens back to the days of Clinton fighting with Gingrich, or the last years of the Bush 43 presidency. In these arrangements, Congress can act as a unified partisan legislative body,6 using the reconciliation process to send partisan initiatives toward the White House for vetoes, and the leverage of total control over the legislature to simply the bargaining structure over appropriations and authorizing bills. And, of course, this arrangement necessarily includes the potential nomination blockades baked into an opposition Senate.

But the traditional divided government arrangement also creates the possibility of a major push against presidential power, not unlike the one I was working on in the summer of 2016 before the election produced a different arrangement and ended the momentum. There’s no doubt the Republicans will be looking to hamstring Biden in a second-term; one look at the proposed Israel Security Assistance Act tells you the GOP is not shy about using the appropriations power to come after executive decisions they don’t like.

More importantly, the groundwork for a lot of this has already been laid. The Democrats in the House twice passed the Protect Our Democracy Act, in the 116th and 117th Congress, which seeks to reform basically every excess of the Trump years in the White House, from emoluments to subpoena authority to the vacancy act to the national emergency act to inspector general protections to pardon authority to, well, freaking everything. Of course, the Republicans balked at this because it was squarely aimed at Trump.

But if Trump loses in 2024, Trump’s gone. And all of a sudden, the window might be open to pass a major package of executive branch and presidential power reforms. You could tweak it plenty of ways; the GOP is hot, for instance, on reforming the rulemaking process and giving Congress more authority to block administration regulations the legislature disagrees with.7 The GOP also seems pretty anti-war right now, which might open up some space for AUMF reform. And I think a lot of what’s in the Protect Our Democracy Act they would actually like, with Biden in office.

The question is whether Dems would go for it in large enough numbers to force Biden to accept it. I have no idea. It wouldn’t be the first time a party passed a bill to reign in executive power and turned right around on it under different conditions. But the House Dems passed this while Biden was president. So there might be deal to be struck. I, for one, would be very much in favor of it.

Recall that Speaker Boehner lost more votes to Freedom Caucus rebels in the 2015 Speaker election than McCarthy did in 2023. But Boehner had a bigger majority—a 30+ seat cushion—and that meant that the Freedom Caucus couldn’t assemble a coalition big enough to control the balance of power.

This includes a concurrent special/regular election in California that will be for the full six-year term but will also include the remainder of the 118th Congress, for the seat currently held by Senator Butler, who was appointed by Governor Newsome to replace Senator Feinstein after she passed away last September. The winner of the election will likely be seated in the Senate sometime during the lame-duck period, after their victory is certified.

Another question is what they do. Some reformers would like to maintain the filibuster but just make it possible for a majority to actually break it, by increasing the intensity necessary for the minority to maintain the filibuster. This is possible, but it has problems. It’s beyond the scope of this newsletter, but something I plan to take up in the near future.

I will strongly defend the right of the Senate to not consider a nomination. In the case of Garland, I think it was bad practice. But I emphatically disagree with those who think the Senate is obligated to take up presidential nominations, or that the president can act unilaterally to fill vacancies when nominations are ignored, absent statutory authorization from Congress to do so.

Now look, Garland was never getting on the Court. McConnell could have gone through the process and the GOP could have voted Garland down in committee or on the Senate floor. There was no chance Garland was getting to 60 votes to break a filibuster. McConnell’s real aim, in my view, was to protect swing-seat Senators (Gardner in CO) from a tough vote on a tough issue. I sympathize with Democrats who are infuriated by the failure of the nomination, but the lack of a vote wasn’t the cause. The votes just weren’t going to be there.

To a degree. A GOP House and GOP Senate are going to have deep divisions over many issues. It’s just not possible to get the House and Senate in lockstep.

I’m on board. My preferred solution is actually to restore the legislative veto, which would require the Court to overrule INS v. Chadha.

There's a number of typos. For instance, here I'd expect to see "mean" not "man":

> I think it depends on what we man by shitshow.

As for the substantive side, could you expand on footnote 4? Why is it a good thing to use the procedural "don't look at things" manner instead of forcing the votes and influencing the elections?