Procedural Notes from a Shutdown

The AMA you mistakenly thought you wanted and will immediately regret reading

Dear Friends,

This continues to be a weird shutdown. There has been a lot of smart analysis about it in the past bunch of days. I would specifically point you to this article by Gabe Fleisher and this podcast by Ezra Klein and Jon Favreau.

I’m switching gears today from straight shutdown analysis. Instead, I’m going to answer some of the procedural/legal questions I kept getting over the weekend. So strap on your nerd-belts, this is going to get really tedious, really quickly.

Can the administration just decide which parts of the government shut down and which continue to operate during a lapse in appropriations?

Yes and no. It’s worth reviewing here the basics of a shutdown.

According to Article I, section 9 of the Constitution, no money can be drawn from the Treasury, except under appropriation made by law. That is, to say, the government can only outlay money that it has been authorized to spend by law. And laws must be passed by Congress. So if the current annual appropriations expire (as they did on October 1) and new bills haven’t been passed by Congress, then no money can be drawn from the Treasury, unless a program or project has an alternative source of funding that hasn’t expired.1

But while the Constitution prohibits money from leaving Treasury in the absence of an appropriation, it doesn’t explicitly prohibit the government from incurring obligations. And while some caselaw vaguely suggests agencies can’t spend money on the hopes of future appropriations, Congress is still theoretically free to empower entities to enter into contracts, hire and employ labor, etc. without an appropriation. Treasury just definitely can’t pay off (liquidate in the parlance) these obligations until there is an available appropriation made by law. Kinda like if you had a working credit card, but no ability to pay it at the end of the month because your checking account was frozen.

So while the disbursement of funds from Treasury is constitutionally prohibited, there’s a separate federal law (the Anti-Deficiency Act, or ADA) that prohibits the obligation of federal resources in the absence of an appropriation, with potential criminal penalties for agency heads who violate it. In effect, the ADA freezes and punishes all use of the credit card, whereas the Constitution freezes the checking account (and suggests you maybe can’t use the credit card).

But the ADA also has exceptions. The main one being for the “safety of human life or the protection of property.” Subsequent opinions of the Attorney General (found in appendices here), opinions of the DOJ Office of Legal Counsel, and guidance of GAO / Comptroller General have (somewhat) clarified what does and does not fall under this exception. Additional exceptions that are widely agreed upon include the Constitutional functions of the branches; Congress and the president need to be able to incur obligations, for instance, in order to work to end the shutdown.

In past shutdowns, OMB opinions have considered the following types of things to fall under the life/safety exception: military and national security, public safety such as air traffic control, care of patients in hospitals and prisoners in prisons (and wildlife at the national zoo), things necessary to protect federal property and continue the functions of the Treasury, and disaster relief, among other things. Under common sense interpretations, the heat can also be left on at federal buildings.

So there’s a lot going on here. The Constitution absolutely prohibits money from leaving Treasury in the absence of an appropriation. The ADA seems to quite clearly prohibit the incurring of obligations absent an appropriation, but also provides important exceptions. So there’s always going to be some inherent discretion about what falls into the exceptions, and people can disagree about this in good faith.

But there’s also a bigger fight over the underlying intent of Congress with regard to shutdowns and the ADA. Prior to the Attorney General opinions in 1980 and 1981 (known as the Civiletti decisions), most agencies didn’t stop operating at all when there was a funding gap; they just liberally interpreted the ADA and decided Congress didn’t intend for them to cease operating. The 1980 and 1981 opinions took a much stricter view of the ADA; that’s really when the modern shutdowns began.

Congress somewhat clarified the nature of the life/safety exception things with an amendment to the ADA in 1990, but arguably the underlying issue of whether there even needs to be the shutdown as most people understand it—the furlough of federal workers and the closing of some agency activities—is open for debate.

In theory, the Justice Department could update their interpretation of the ADA and go back to the pre-1980 view. That doesn’t sit well with a basic reading of the ADA, but it also has some backing of congressional intent at the time, and even GAO had the odd position prior to 1980 that agencies were violating the ADA when there was a lapse in appropriations, but Congress still didn’t intend them to shutdown.

Congress could, of course, clarify all this with new legislation, but don’t hold your breath. And the courts could make definitive rulings about the constitutionality of incurring obligations absent an appropriation. Again, don’t hold your breath.

But until either of those things happen, a lot is at the whim of interpretation. And even if GAO or other congressional watchdogs find the administration’s interpretation to be ridiculous (GAO found lots of ADA violations by the administration in the last shutdown, nothing came of it), absent a forceful Congress there’s not a whole lot that can be done to check it, especially in the very short-term during a lapse in appropriations.

The other issue here is that the administration often has the ability to move existing appropriated money around, and that can give them a lot of discretion about keeping things open. Many agencies have multi-year money (Congress regularly provides two-year or five-year, or so-called “no-year” money that lasts until spent) and/or money from non-appropriated sources (for example, the courts collect filing fees and Congress has authorized them to use it to supplement their annual appropriated funds). This allows agencies to continue to temporarily operate—they have an appropriation (or non-appropriated funds) available by law!—even if their regular, annual appropriations have lapsed.

Congress also often authorizes (but doesn’t require) the administration to move appropriated money around from one purpose to another (called transfer authority) and often provides that non-appropriated funds can be used for a wide variety of purposes, so that gives the administration flexibility to, for example, close the national parks (on account of them not having their appropriation) or keep them open (by transferring appropriated multi-year money, or non-appropriated sources of funding to the parks that is available, but not required, for that use).

That’s a good setup for our next question…

I see that troops are now going to get paid instead of missing a paycheck during the shutdown. Can Trump just decide to pay uniformed soldiers if Congress has not passed a bill specifically appropriating money to do so?

No, the president cannot just decide that troops will get paid absent an appropriation made by law. Military pay is not a special category of funding in the Constitution; the provisions barring money leaving Treasury absent an appropriation apply exactly the same as any other expenditure. That is not in question.

What is also not in question is that uniformed soldiers are an exception to the ADA, meaning that there is no doubt that uniformed personnel can continue to work and incur obligations without violating the law. They are the most obvious example of an “excepted” employee under the life/safety provisions of the ADA. But even though they continue to work, they will not get paid for their work until there is an appropriation.2

Not surprisingly, this has caused some political pain. Not paying soldiers doesn’t sit well with many people (me included), and a lot of people thought that a missed paycheck (the first missed payday would be Wednesday, 10/15) might be a pressure point to move Congress toward a resolution of the shutdown (in the 35 day shutdown in 2019, the Defense appropriations bill had already been enacted, so there was no issue). There is also a bipartisan bill in Congress to provide appropriations for servicemembers during the shutdown. But that bill has not passed.

But over the weekend, the administration announced that it had found a way to pay the troops and that they would not miss a paycheck. They did not specify how exactly they found the money, and some observers were a little skeptical (not unwarranted, given how fast and loose this administration has played with a lot of law) that the ultimate mechanism would be rock-solid-obviously-legal.

In theory, paying the troops requires two things. First, an appropriation that has not expired; that is, money Congress approved that is available beyond the end of fiscal year 2025. Second, transfer authority that allows the administration to shift that money from its current account/purpose to the account that covers the pay for uniformed servicemembers.

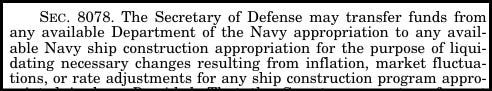

The basic idea is sound and not farfetched. There are multi-year appropriations all over the annual Defense appropriations acts, and there is also transfer authority all over the place as well. Here’s an example of multi-year money in the FY24 Defense act (which is continued in the FY25 full-year CR):

Note that this is two-year money (we are looking at the FY2024 appropriations, which would normally run through September 30, 2024 but here is being provided to run through September 30, 2025. And note that the full-year CR we are currently operating under, which provides funds on the same basis as the FY2024 act, provides that multi-year money continues to be multi-year money:

So that account of $27B (or whatever is left of it) is live two-year money right now. And as I said, there are lots of these multi-year accounts in the Defense bill.

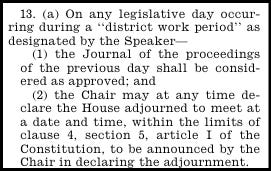

There are dozens of transfer authorities in the Defense appropriations act. Here are some examples:

Not all transfers could get to the military personnel accounts—the last example above, for instance, limits the transfer to Navy ship construction—and the terms of the transfers are often further restricted by law. If you look at the second example, it limits its applicability upon transfer to the “same time period…as the appropriation or fund to which transferred,” which might preclude it from being used in an account that only has expired FY2025 money and no current FY2026 funding.

For the transfer we are interested in, the administration stated that the money would come from $8 billion of two-year Research, Development, Testing, and Evaluation (RDTE) funds. RDTE is in Title IV of the Defense bill, so we would be looking for existing multi-year money in Title IV, plus transfer authority wide enough that the money could be moved to the accounts in Title I (Military Personnel) that fund the pay for the servicemembers.

I have not found an exact account and transfer authority the administration could be using for this, but I also haven’t looked super hard; you can’t just look in the most recent Defense bill, because the money could (in theory) be no-year money from quite some time ago. There’s also a lot of arcane language and details I’m not familiar with; defense appropriations is complicated, and it was never something I worked on when I was on the Hill. So I do not have an answer.

What I do know is that the money eventually runs out. It’s not cheap to pay all the uniformed soldiers. The Military Personnel title of the Defense bill is in the $180B range annually, including reserves and national guard and Tricare. So we are talking billions of dollars a week; even if the administration has found some existing appropriations and the proper transfer authority, there’s no guarantee that the same source will be available for the next paycheck.

I see that Member-elect Grijalva has not been sworn-in yet. Can the Speaker just decide to not swear-in a Member?

Not without bringing the House essentially to a halt. A proposition to swear-in a Member-elect is of unusually high privilege in the House, meaning that it takes precedence over virtually anything else the House is doing.

In past practice, it has had priority over a pending matter ordered to a vote, it has been administered during a roll call vote, it can occur without a quorum present, it does not require the Speaker to be present (he/she can designate a deputy), and it can be delegated to a non-Member and does not need to take place in the House chamber. In one case, it even took precedence over an attempt to adjourn, which is truly remarkable.

So whenever the House comes back into session and attempts to do anything, the swearing-in of Member-elect Grijalva will have precedence. That said, if the House is not in session, there’s no practical way to force the issue. And—as we will see in the next question—the Speaker has dangerously powerful authority under the current rules to keep the House out of session.

Now, the House always has the authority to alter its rules and ignore its own precedents. If a majority of the House wanted to make the swearing-in of a Member not have unusually high privilege, it would be within its right to do so. At some point, however, this would run up against the constitutional boundaries of the House refusing to seat a Member-elect.

The courts generally stay out of disputes about House procedure—which makes sense given that Article I, section 5 allows the House (and Senate) to set their own rules—but the Court has also ruled that a duly-elected Member who meets the constitutional qualifications may not be excluded from the House by a majority.3 If a Member-elect who met the qualifications and whose election was not being contested (which is the case with Grijalva) was denied a swearing-in and was missing final passage votes on legislation, my guess is that the courts would quickly step in and force the House to seat the Member-elect.

None of this excuses Speaker Johnson, who keeps making excuses but should agree to just swear-in Grijalva during one of the pro forma sessions the House is holding. There’s no impediment to that, and it really is starting to look like Johnson is doing this specifically to delay Grijalva from joining the discharge petition related to the Epstein files, where she would be the 218th signature and would get the process moving for securing consideration on the House floor.

That’s a bad look for Johnson and a bad look for the House, but there are bigger fires being played with here. Toying with the swearing-in of duly-elected Members is the kind of hardball that could cause a real constitutional crisis at the beginning of a new Congress. I expect this current situation to resolve very easily—when the House does come back for legislative business, I would be shocked if Grijalva wasn’t immediately sworn-in—but the entire charade of delaying her swearing-in is terrible practice for the House, and a terrible precedent going forward.

The House has not convened for anything besides a pro forma session since September 19th. Can the House just stay out of session during a shutdown?

The House can absolutely stay out of normal session during a shutdown. The only constitutional requirements on the House convening are (1) the Congress must assemble at least once a year (Article I, section 4; 20th amendment, section 2) and (2) neither House can adjourn for more than 3 days with the consent of the other (Article I, section 5).

So as long as the House meets in pro forma session every third day right now, they are under no constitutional obligation to do anything else. And a pro forma consists of very little: often just calling the House to order, approving the Journal, saying the Pledge of Allegiance, and then immediately adjourning for another three days. A pro forma session of the House isn’t actually a distinct thing; it’s more a term of art to describe a short session where the norm is that no votes will be taken and minimal legislative business will be conducted.

None of this is particularly problematic; if the House does not want to be in session, that is up to the House. Where a problem does arise—both in theory and I think perhaps right now in practice—is if the House does want to be in session but the Speaker is preventing that from happening. That would be a very bad situation indeed; if a majority of legislators wanted the House to be operating, it should be operating.

But how is that even possible? Your first instinct—not wrong—might be to say, “Matt, you always say the House is a majoritarian body, how could the Speaker prevent a majority from even getting the chamber into regular session?”

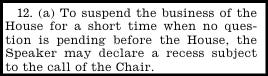

The answer is that the House has given the Speaker a series of authorities in the rules that essentially provide him/her unilateral control over whether the House is in session. These include Rule I, clause 13, which provides the Speaker with the authority to, at any time, declare a “district work period,” which unlocks a second authority, which allows the Speaker to declare the House adjourned to meet at any date/time within the constitutional restrictions on single-house adjournment. A second authority, found in Rule I, clause 12(a), allows the Speaker to declare a recess subject to the call of the chair whenever there is no business pending.

The problem with these provisions is that they create scenarios where the full House cannot procedurally overrule the Speaker. Once the Speaker declares the House adjourned or in recess, there’s no way to challenge that action. And when the Speaker calls the House back into pro forma session (or back from recess) in order to fulfill the constitutional obligation, he/she can simply use these authorities again to go right back into adjournment/recess. Again, without the ability of a majority of the House to object.

Indeed, we have seen that last week with the Grijalva swearing-in. Some Democrats took to the floor during the pro forma session in order to try to bring up the swearing-in, but the chair simply adjourned the House on Rule I, Clause 13 authority without recognizing the Members. And there’s nothing procedurally wrong with that. (The Democrats could try to get recognized prior to the pledge, as ringwiss points out, but there’s no reason to believe that would work either).

More worrisome is that, by my count, there might be a majority (217 of the current 232) in the House that would prefer to be in session right now, or at least enough (216) to block an adjournment vote. If we assume all 213 Dems would like to be in session, plus Republicans (1) Rep. Massie, (2) Rep. Taylor-Greene, and (3) Rep. Kiley, that sure looks like the 216 who would oppose a motion to adjourn, if the Speaker would required to get the House’s consent.

Now, what’s the upshot here? It’s definitely true that those three Republicans might prefer to be in session, but it’s also the case that they might not be hellbent on it, and would support a leadership motion to adjourn because they have other goals and don’t want to get sideways with their party. And it’s also true that if huge numbers of Republican Members wanted to be in session, the Speaker would have little ability, politically, to stop it from happening, regardless of technical authority.

But my concern here is not about the shutdown, it’s not about the Grijalva swearing-in, and it’s not about the Epstein files. It’s a risk-reward calculation about much more dangerous situations. The benefit of allowing the Speaker this authority is very small—it saves us a 10-second unanimous consent request most of the time (“I ask unanimous consent that the House adjourn until noon on October 17”) or, if people are being feisty pains-in-the-ass, a roll-call vote or two in the House on a motion to adjourn and a motion to fix the date and time certain of adjournment.

The downside of this authority is that there are true nightmare scenarios that the Speaker could create with it. Here’s a (modestly) far-fetched one: no one is disputing the results of a presidential-election, but the Speaker won’t allow the House to come into session to count the electoral college votes? The new House comes in on January 3rd at noon, elects a Speaker, and adopts its rules. That Speaker immediately adjourns the House under the unilateral authority. And won’t let it back into session. And continues this behavior until January 20th. Guess who becomes Acting President at noon on the 20th: the Speaker of the House.4

The flip-side of this issue is a proposal by Rep. Moskowitz to require the House to be in session during a shutdown. Whatever the merits of that idea are as a substantive matter, it’s just extremely hard to draft a set of legislative procedures that would prevent the House from adjourning if the majority wants to adjourn. The Moskowitz proposal seems to be more a messaging bill than a serious piece of thought-out legislation—it doesn’t even shut off the Speaker’s unilateral adjournment authority, and it also would leave the House in session 24/7—but even a well-crafted resolution would have trouble keeping the House here against its will; a majority could almost certainly write a special rule to circumvent even the most tightly-drafted anti-adjournment legislation.

Can Majority Leader Thune prevent Senator Schumer from getting a vote on the Democrats’ alternative Continuing Resolution to reopen the government?

Pretty much. For the past two weeks, the Senate has been taking votes on two separate Continuing Resolutions—a House-passed version that is supported by the GOP Senate, and a Senate Democratic alternative. Neither of them have been successful in securing cloture (the 60-votes required to end debate on either measure; the GOP version failed 54-45 and the Dem version 47-50 last Thursday), and so we’ve seen a bunch of rounds of voting on them, either in the form of direct votes on cloture petitions related to the legislation, motions to reconsider the the cloture votes on the legislation, or direct votes on motions related to the legislation setup by unanimous consent agreements.

But the procedural rules of the Senate do not put the majority under any obligation to allow this. And late last week, Majority Leader Thune indicated that he was going to take procedural steps to preclude the ability of the Minority Leader Schumer from getting votes on the Democratic alternative. I’m frankly surprised that it took so long to get to this point; I figured the Republicans would want to have continuous votes on their CR so they could show how the Senate Dems were blocking the reopening of the government. By allowing the side-by-side votes and including the Dem alternative, it seemed to very much muddy any argument about who was preventing the reopening of the government.

At a technical procedural level, what Thune will do is prevent Schumer from ever making a motion to proceed to consideration of the Democratic alternative. Without a pending motion related to your bill, there’s no way to file a cloture petition in the Senate, and without a cloture petition, there’s no way to force a cloture vote on your motion. Thune will do this by moving to proceed to consideration of the House-passed CR, and then not withdrawing the motion after he files his own cloture petition.

With one motion to proceed pending, a second cannot be made; Schumer would have to find a way to dislodge the Thune motion to proceed in order to make his own. Absent the votes to table it—which he doesn’t have, naturally—it’s not getting dislodged. Thune can then just wait for his cloture petition to ripen (it takes two days), and get a vote on the GOP CR without having to have the companion vote on the Democratic alternative.

There are procedural complications to this. If the GOP wants to do anything legislatively besides wait out the motion to proceed on the CR, it takes some additional careful arranging to avoid giving Schumer an opportunity to make his motion to proceed.5 And if Schumer retaliates by denying unanimous consent to a whole bunch of routine stuff that normally gets accomplished (or avoided) by consent, it could cause further headaches and required procedural maneuvering.

But the underlying theory is sound; if Thune and the GOP want to avoid votes on the Democratic alternative CR, they have a clear procedural path in the Senate to do so.

Such alternative sources generally fall into three categories: first, mandatory programs (such as Social Security and Medicare) that do not rely on annual appropriations for funding; second, programs that have multi-year appropriations from previous annual appropriations bills; and third, programs that have non-appropriated sources of revenue that Congress has authorized for use, such as filing fees in the courts.

In the event that no appropriation was ever made to pay them for their work—for instance, if Congress decided to abolish the military rather than pass an appropriations bill for them—those who had incurred an obligation would likely have legal recourse in the courts to collect the money the government owed them. In some sense, this is what the word obligation means.

The House has the unquestionable constitutional right to expel any Member, but that requires a 2/3 vote.

There are lots of rejoinders to this, both procedural and political. But at the very least, it would be pure chaos.

Indeed, the consideration of the NDAA as it went last week would have been tricky if they were also trying to prevent Schumer from being able to get a cloture petition to the desk on a pending motion to proceed to the Dem bill.

I for one am excited for President Johnson to seize the reins in 2029. I always knew that House of Cards was realistic.

“So if the current annual appropriations expire (as they did on October 1) and new bills have been passed by Congress, then no money can be drawn from the Treasury”

I’ve always thought that “new bills…passed by Congress” should imply that Congress intended for appropriations to be made available to implement the law. Only lawyers (and I say this as a lapsed one myself) could say “well just because Congress passed a law requiring that X happen, it doesn’t actually mean X can happen.” Same with the debt limit. If Congress wants to spend less money, it can repeal the legislation that requires the spending of the money in the first place. I know this is a fantasyland I live in, but still. My kingdom for a government structure that actually makes at least a little bit of sense.

Thank you for your write-up on all this, it was very helpful to understand some of the details and peculiarities of what’s going on!