Moderation has multiple flavors in politics

And Some Other Links Worth Pondering

Dear Friends,

Here are sixteen items I found interesting reading or listening to this week. All are recommended, even though I often found myself in disagreement.

#1. Matt Yglesias, Folding A Winning Hand Isn’t Moderation. There’s an ongoing fight between online nerdy progressive and abundance-type Democrats about whether the party should moderate in order to do better in elections. But what this article mostly solidified for me is that it’s really hard to pin down what exactly makes someone a moderate, or what exactly it means to be moderate. I discussed this with my public policy undergrads last night, and we came up with at least eight distinct dimensions of moderation, many of which correlate at times but not always:

You have a middle-ground position on a policy issue(s). This feels like the classic definition. Some people are hardcore pro-choice. Some are hardcore pro-life. If you don’t like abortion but think it should be legal in the first trimester but with waiting periods and such, you’re a moderate on abortion. Or take Lincoln on slavery in 1858. Doesn’t like it. Wants to prevent its expansion westward. Not in favor of immediate abolition where it exists. And if you repeatedly take moderate positions on individual issues, you yourself are a moderate.

You buck your party on important issues. You are a congressional Democrat, but you are strongly pro-gun and pro-life. Neither of those positions are ideologically moderate—you are the real deal on life and guns—but since you fall in the middle on some collective ideological scores/scales and you vote with both parties at times, and your own party has to work hard to keep you from bolting at times, you are a moderate. In the aggregate, this is the type of moderation (I think) Yglesias likes and evangelizes: Democrats should just dump some of their really stupid unpopular positions—like backing trans athletes in women’s sports and hating on cops—in order to create a more moderate bundle of policies and (hopefully) attract more voters. I tend to agree with him about that.

You don’t like either political party and/or you are a swing voter. This applies more to voters than elites, and overlaps with the related concept of the “independent.” Your policy positions aren’t necessarily moderate, but the collection of them makes you dislike both parties and feel alienated from each of them. Maybe you want a higher minimum wage and you really dislike immigration but you hate the ACA and want handguns banned and you voted for Clinton and then Trump. You are orthogonal to ideology and/or at least the partisan organization of issue.

You are a compromiser. This is the first dimension of moderation that is theoretically completely independent of ideology. Some people in Congress like to cut the deals and get half a loaf, and some people are true believers who refuse to bargain. This is obvious to anyone who’s ever been in any group decision, anywhere; people have different preferences about the value of coming to an immediate policy outcome, different time horizons for success, and different tolerations for anger and gridlock. One structural feature of Congress is that certain jobs more or less require compromise. Appropriators and leaders come to mind. Tom Cole is not an ideological moderate. But he goes for half a loaf all the time. Kevin McCarthy was not an ideological moderate. But he had to cut the deals. And this is why they draw the ire of their party hardliners.

You are a pragmatist. This follows from having a compromise temperament, but I think is distinct. One way to think about it is as a preference for incremental policy gains over holding out to try to win bigger political victories that might unlock more sweeping change. The eight Dems who backed the CR preferred a deeply compromised outcome over holding out for some plausibly-better outcome down the road. Another completely different angle to this is that people driven by or responsible for on-the-ground outcomes often end up being moderates. It’s why it’s easier to not be a moderate in Congress, and harder in the governors’ mansions. The executives have direct responsibility for on-the-ground outcomes, the legislators don’t. So during COVID, we saw a lot of Republican governors take moderate positions, and a lot of Republicans in the House minority take outlandish extreme positions.

You are a Burkean conservative. One hallmark of many moderates is that they basically think the system works. They may not love how the elections went and they may have lots of ideas for policy changes, but at the end of the day they believe in the status quo process and the existing institutions of governance. And they are generally scared of the people—left or right—who explicitly want to burn it all down, and skeptical of the people who seem a little too comfortable with things that might risk burning it all down in order to secure policy gains. For many of these moderates, Trump is scary but so is Mamdami.

You represent a swing-district that went the other way presidentially. Jared Golden and Don Bacon both seem like moderates on many of these dimensions, but they also are practicing a distinct type of electoral politics, something like “I might fit well with my constituents on policy, but I belong to the wrong party for my district and I have to deal with that” politics. Note this is different than being a pro-life, pro-gun Blue Dog Democrat in Georgia in 1990, where you might perfectly represent and fit in with your district, both on ideology and party affiliation. Golden and Bacon need to go out of their way not just as a matter of issue positioning, but also as a matter of partisan identity in both DC and Nebraska/Maine. And their entire state of being as political creatures in the party system forces them to concentrate more energy on re-election and all that entails.

You are a policy wonk. This is a huge phenomena in DC. If you really dig into an issue that you care about, it eventually boils down to a set of trade-offs that almost always makes it more complicated than the interests on each side of the issue publicly want to admit. And so you naturally begin to see things both ways. And this sometimes makes you a bad/weird candidate on the stump because you end up trying to explain stuff in way too much nuance. Obama and Romney both suffered from this, and it’s why the 2012 election is so unique: two moderates threw health care white papers at each other while everyone else tried to pretend they were crazy extremist partisans.

A lot of this is not directly related to the question at hand for Yglesias and his interlocutors on the internet and in the Democratic party, in part because the question of how a party moderates is somewhat different than the various ways an individual might be a moderate.

But I do think this gets at Yglesias’ frustration at the individual Senators who chose to cut the deal with the GOP to reopen the government; Matt is entirely correct that that they weren’t the most obvious policy moderates in the Senate, and plenty of ideologically more moderate Dems did not vote for the deal. But the ones who did had a a lot of markers of other types of moderation, especially the temperament of compromise and pragmatism. And in some cases, the structural backgrounds. Shaheen and Durbin are appropriators. Hassan, Shaheen and Kaine are former governors. King, Rosen, Cortez-Masto, and Fetterman are from obvious swing states. In some ways, it all makes sense.

#2. Central Air podcast on the Epstein files release. Like the participants on the podcast, I’m more or less bored by the Epstein saga. The whole thing feels way too much like banana-republic politics. There’s a Benghazi political feel to the Democrats picking up the Epstein conspiracy and running with it purely to make political hay, especially after all these years of it being a looney rightwing story. I don’t begrudge them their political grist—politics ain’t beanbag—but I just can’t bring myself to care. If there were people left to prosecute, DOJ would have almost certainly done it by now, under one POTUS or another. It’s a titillating story and a populist dream to see such awful elite behavior and condemn it, but not much else at this point.

I also think there’s a fair amount of potential harm. I don’t have any specific sympathy for people like Larry Summers, but it’s also plainly obvious to me that people found to be doing sleazy things or having friendships with awful human beings shouldn’t be exposed by the government absent some actual charge of criminal behavior. And it’s bad precedent to blow up peoples’ privacy simply because their unethical but legal behavior became known to the government in the course of a criminal investigation. I couldn’t care less what happens to Larry Summers or his career, but there’s something icky about the government’s role in his demise at Harvard.

#3. House and Senate passage of the Epstein release bill. Now this is interesting, and instructive as to the dynamics of legislative politics. After all these months of wrangling, the bill passed the House 427-1 and the Senate by unanimous consent. This was a classic example of how roll call votes often distort the underlying politics and preferences on an issue. The key is that legislators have two uses for their vote in the chamber: (1) to affect the outcome of the vote; and (2) to signal their position on the matter. Often these are tied together: if you hate slavery, want to restrict slavery, and want to signal that you hate slavery and want to restrict it, you vote in favor of the Wilmot Proviso.

But just as often, the two things aren’t necessarily linked. For one, a really easy way to defeat a proposal is for it to never get to the floor. This is especially true if you don’t like something but don’t really feel like publicly opposing it. And Members have lots of gradations of support for things beyond simply their vote. Setting the agenda—both positively and negatively—is a key power of the majority party in the House, and making sure that votes don’t come to the floor on issues the Members of the majority want to avoid is a basic competency of the leadership.

The flip side of this, of course, is that when things do come to the floor in the House, it’s almost never in doubt that they are going to pass. And once you know something is going to come to the floor and is going to pass, your vote is no longer about affecting whether or not it is going to pass; now all you are doing is signaling your position about something that is going to happen. And that changes your calculus from “do I want this to pass” to “what does this signal mean in the context of forward-going politics.”

And that’s what creates the “Vote No, Hope Yes” caucus on tough votes, and the easy votes against big deals. And it’s also what herds people together and creates 427-1 votes on issues that didn’t have enough strength to get to the floor a week earlier. There are just a lot of issues where you don’t want to be on the wrong side of them once they are going to happen. So all of the opposition goes into keeping it off the floor, but once that dam breaks, everyone votes for it.

I’m going to do a whole piece on roll call votes sometime soon, because I think they are generally overused in political analysis of congressional behavior, but it’s important to see them for what they are—decision devices and signaling devices.

#4. Molly Reynolds on the power of the purse. One annoying feature of the end of the shutdown is that a lot of the challenges to administration actions are now moot, either legally or politically, but they will now be filed away in the administration toolkit as political precedents. Decades down the road, when all of the fight and the opposition to them is lost in the sands of time.

#5. Max Spitzer on the origins of the Speaker’s adjournment and recess authority. I’m on the board of our neighborhood pool—seriously folks, hyperlocal politics is the place to be—and we were working on revising our bylaws this week, and one set of decisions was about supermajority voting thresholds for various things, like special assessments or literally dissolving the corporate-membership structure, and the related question of whether this stuff should be a supermajority of a quorum or a supermajority of the whole membership. As you would expect, it gets pretty painful for everyone 20 minutes into a discussion of such things.

And there’s just a very basic sense in which it’s totally unimportant in practice and a waste of time—when is anyone going to try to dissolve the corporate structure of the pool!—but I think you really want to nail this stuff down, because when it does come up you will be glad there’s no ambiguity and that you thought through worst-case scenarios, because the substantive climate in which something like this arises is almost inherently not going to be a calm, reasoned discussion of procedure. The Speaker’s unilateral adjournment/recess authority is a ticking time-bomb, we got a mild sneak preview of it with the shutdown, and we should patch so we never have to deal with it in the wake of it exploding.

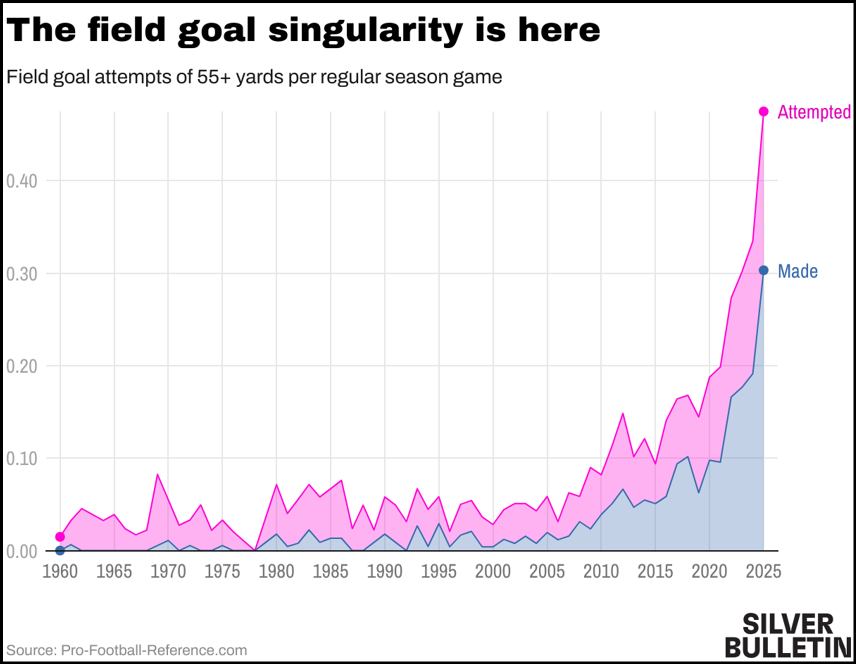

#6. Nate Silver on how much football has changed. Interesting throughout. And you don’t need Nate’s analysis to notice the basic change. It’s obvious. You sit down and watch an NFL game this year and it doesn’t even feel remotely like the sport as it was in the 1990s, or for that matter, 2023. One general thing to note here is how much small changes in rules or tactics—like the yard-line a touchback comes out to—affect the global strategies of the participants. Another is how particular improvements in player skill—namely kicking ability—is almost totally asymmetric in favor of offense. Combine those two things and the percent of drives that end in a score has skyrocketed, and the resulting cascade of major strategic adjustments is almost incredible. Going for it on 4th down. Favoring safe short passes and runs over long throws. Trying not to leave teams even 30 seconds of time at the end of halves.

The other side of this is the fan experience. Every major sport has undergone a strategic revolution in the analytics age, but some are more visible than others. A baseball game looks roughly the same as it did 30 years ago. The NHL has opened up quite a bit, but that’s mostly on specific large rules changes in the 90s/00s. Basketball and football, on the other hand, are fundamentally different. I used to think high school football was the most exciting version of the game, because the kickers routinely missed extra points and teams always went for it on 4th and 7 from the 18 or whatever in the 1st quarter, and that stuff literally never happened in the (comparatively boring) NFL. But now things have largely reversed; many high school kickers are competent from 30-35 yards and the game looks more like the old boring NFL, and the modern NFL kickers are so good that teams consider going for it on 4th down on their own half of the field because making it probably worth 3 points and punting is so much more likely to produce opposing points.

#7. Tyler Cowen, interview with Blake Scholl on air travel. One of the most fun and interesting podcast episodes I’ve heard this year. This sidebar on Congress and why defense stuff is built all over the country instead of in a central location is simultaneously correct, naive, and maybe changing:

SCHOLL: Congress. Yes. This is a congressionally optimized supply chain because the way you get a defense program to become a program of record is you maximize the number of votes. You put one process step in every congressional district. By the way, this will be very, very terrible if we actually go to war.

COWEN: How do we fix that systemically? We’re going to have Congress, no matter what. You and Jennifer Pahlka get together and come up with what kind of plan?

SCHOLL: Nobody wants to be the only one who cuts things in their home district. I also think about this in the shower. Maybe I shower too much. I think the Newt Gingrich playbook is underrated. Congress runs together on one platform, and they all agree to be in on something, I think might actually be really important. It doesn’t necessarily have to be partisan. Imagine if we had a bipartisan campaign for the next Congress, and everyone agreed on a few things that are like, “Hey, we’re going to all be in this together. Maybe we’re going to balance the budget, and maybe we’re going to change defense procurement in some way that it doesn’t fix this effect.”

I don’t know what the exact solution is. I think a congressional team all in on the same agenda, because everybody could say, by the way, obviously, we can’t be porking every district. So long as that’s a district-by-district decision, it gets perpetuated. I think there needs to be a team or a theme, and I think this actually could be sold to the public because at a certain level, it’s obvious that it needs to be fixed, and obviously good for America.

Correct that you build support and votes by localizing benefits—I think the space station was literally built in 400+ House districts. Naive that this can be undone by simply developing a bipartisan campaign to avoid it. And perhaps changing now that American politics is nationalized much more than it was a generation ago. Congress looks and functions a lot less like an incumbency-protection scheme than it did 40 years ago, Members have far less ability to drum up opposition party support in districts via local projects, and on major party agenda items we see some evidence of Members choosing party over district. “All politics is local” is far from dead—far from dead—but it isn’t the no-brainer reality in Congress that it was in the 1970s.

#8. Gabe Fleisher on historical uses of the discharge petition. One might ask why the discharge petition rules even exist—why would the majority party provide a way for a tiny handful of their Members to combine with all of the minority in order to do hijack the floor agenda and do something 90% the majority party Members dislike? One functionalist answer is it routinizes, slows down, and makes highly visible a process that could always be done on the fly by a rogue faction anyway; it’s easy enough for a handful of majority party Members to combine with the minority and stop all leadership agenda setting on the floor dead in its tracks until its demands are met, so why not provide a mechanism for doing it that makes it more predictable, observable, and gives you more time to head it off. Also note that the sharp rise in successful discharge petitions as of late might be due to things like cross-party dissatisfaction or back-benchers becoming more strategic and willing to employ hardball, but probably can be explained almost totally by the thin majority margins in the House.

#9. Richard Hanania, on the GOP, racism, nativism, and economics. The title of the article—Should the GOP be more explicitly racist?—is bombastic and misdirecting, but the actual discussion is enlightening. The political problem of having to pretend nativism is about economics and not culture/race leads to obviously dumb economic policy proposals like trying to limit H1-B high skill visas, and precludes the most obvious post-liberal path nationalist conservatives could tack to win-win (from their perspective) on the issue—just endorse an illiberal foreign-worker system like those of the gulf states. Get the economic benefit and the nativist hierarchy. To be clear, this is a normatively good political problem—I’m not wishing conservatives had the right political climate to run on an illiberal foreign-worker platform—but it is helpful in understanding the thicket created by contemporary nativist sentiment and economic reality.

#10. Modestly-related: James Traub on the tougher citizenship test. Count me as a fan. I’m sure some in the Trump administration see this as a way to slow the process of creating naturalized citizens, but cementing deeper civic knowledge into Americans is a worthy goal. If you don’t see America as a blood-and-soil nation but instead a community bound together by a common creed, we have to have ways to nudge forward that creed. Making the entrance exam tougher isn’t going to miraculously change anything, but it’s directionally correct. It’s the same reason I find the singing of the national anthem at high school sporting events a good idea, and find it odd that so many lefties find it distasteful.

#11. Modestly-related: Kelsey Piper on student grades having almost no signal value at this point. There’s a tornado of interests here—administrators, parents, students, teachers—that have selfish incentives to either want inflated grades or find it too exhausting to fight with those who do. One sidecar is the collective action problem. If other high schools or colleges are inflating grades, what happens to our students/children in the eyes of colleges an employers if we don’t join in? Reputational effects might work, but that seems dicey. And so you get systems like the one I observe in Fairfax County, Virginia: rolling gradebooks and bonus points for honors/AP classes and endless grade grubbing and thus an equilibrium where a 4.2 GPA is neither particularly standout nor great evidence of student achievement. Note this signal problem is in theory distinct from the question of learning outcomes, but those are falling too and so it’s hard to see them as unrelated.

#12. This chart of the “shrinking” middle class. Nothing sets off people in my world more than discussions surrounding three indisputable facts: (1) global extreme poverty has declined astonishingly over the last 30 years; (2) Americans have become significantly more wealthy in the last two generations; and (3) wealth inequality in America has risen and continues to rise.

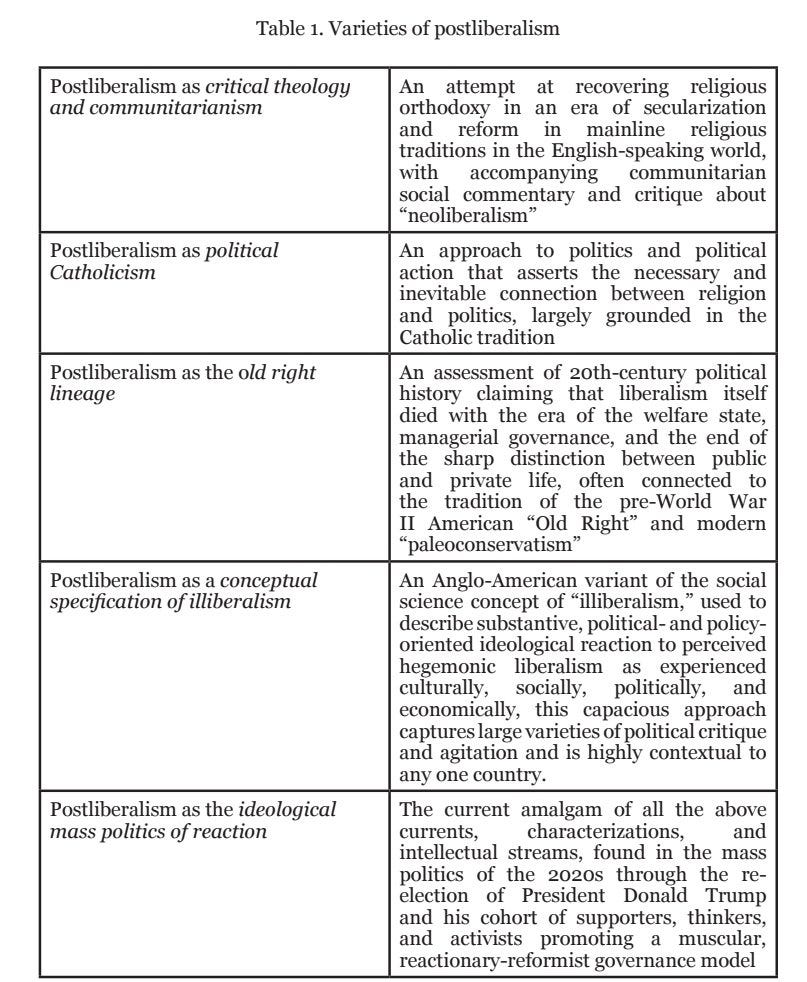

#13. Varieties of post-liberalism. A useful chart/explainer.

#14. Daniel Schuman interviews James Curry. A dimension of legislative politics nobody really talks about is access to information. I’ve said it before, but the best way to get what you want at the PTA meeting is to ambush people on an issue they barely knew was on the agenda. Just show up with a fully prepared presentation, including a handout with a crisp analysis. Just be polite but firm and they will never know what hit them and you will get your way.

The leadership version of this in Congress is to guard the legislative text and the negotiations from the rank-and-file (and, often, the public) for as long as possible. I had direct experience with this at the House Appropriations Committee. We wouldn’t let the other Members of the subcommittee see the draft bill until mere hours before the subcommittee markup, and we wouldn’t let them take copies of it away with them after the markup. We’d take their input beforehand, of course, and try to make sure their priorities were in the bill, but we weren’t going to let them pick it apart line by line for a week before the markup. Insane!

And once your draft bill had to be fully public—back then 72 hours before the full committee markup—you wanted it on the House floor ASAP, lest the vultures around town have too much time to organize against every little provision they didn’t like.

#15. Aphantasia. This is the condition in which you can’t see mental images, and I have a moderate case of it, like between #3 and #4 on the chart at the beginning of this article. The weird thing is that I had no idea about it until maybe 5 years ago when I stumbled across something on the internet—I just assumed everyone saw mental imagines the same as me. And the fact that we don’t seems both creepy and important, adjacent to the stoner conversation idea that maybe we all see the various colors differently. I’m with Matt Yglesias that the linked article focuses too much on the downsides, but the more profound idea for me is that there are aspects of human experience that differentiate us in very basic ways and possible with profound consequences, that we still barely understand or even recognize.

#16. Tyler Cowen on American democracy and why so many people have mistakenly exaggerated its death. I am long on record that what we are seeing in the U.S. right now is much more likely to retrospectively look like a (in my view, negative) transformation of the constitutional order within our democracy than a major erosion of the basic democracy itself, so this confirms my priors and YMMV. Tyler offers five explanations for the mistaken death pronouncements, but an obvious sixth is that many of the pronouncements are strategic, either for purposes of political influence or—more often—for in-group signaling dynamics, a liberal version of the MAGA based ritual.

On democracy, the other thing Tyler is missing is the "Y2K phenomenon": warning about the problem is a spur to doing the needful to avoid it, even though when the problem is avoided, those who did that necessary warning will be derided as Chicken Littles. If indeed US democracy survives the next few years in good shape, it will be in large part because of the lawsuits, citizen movements, etc motivated by the fear that it might fall.

Great stuff, as for moderation I think the whole "Chuygate" (or whatever we are going to call it) thing with MGP shows another variant of no. 2 where you "show moderation by being uncompromising on a principal" thus differentiating yourself from your group*. Maybe MGP has really strong personal opinions on this but ballot games are nothing new in politics in general and Chicago in particular (see Obama playing hardball and knocking people of the ballot in his first race for State Senate). Likewise I have a hard time thinking her constituents care much about this one race in a whole another part of the country or that many people outside of the district will care much at all about this next year. But intentionally or not it was a clever bit of politicking in terms of building her brand of "I'm a different kind of Democrat"** especially when various progressives (Jackson etc) got mad and did the whole "Respect your elders girl!" thing. Maybe they were in on the plan from the beginning LOL.

*see also the Mugwumps

**see also her "I live in a house in the woods" stuff, Hakeem Jeffries very much doesn't live in a house in the woods etc